Claire Jarvis

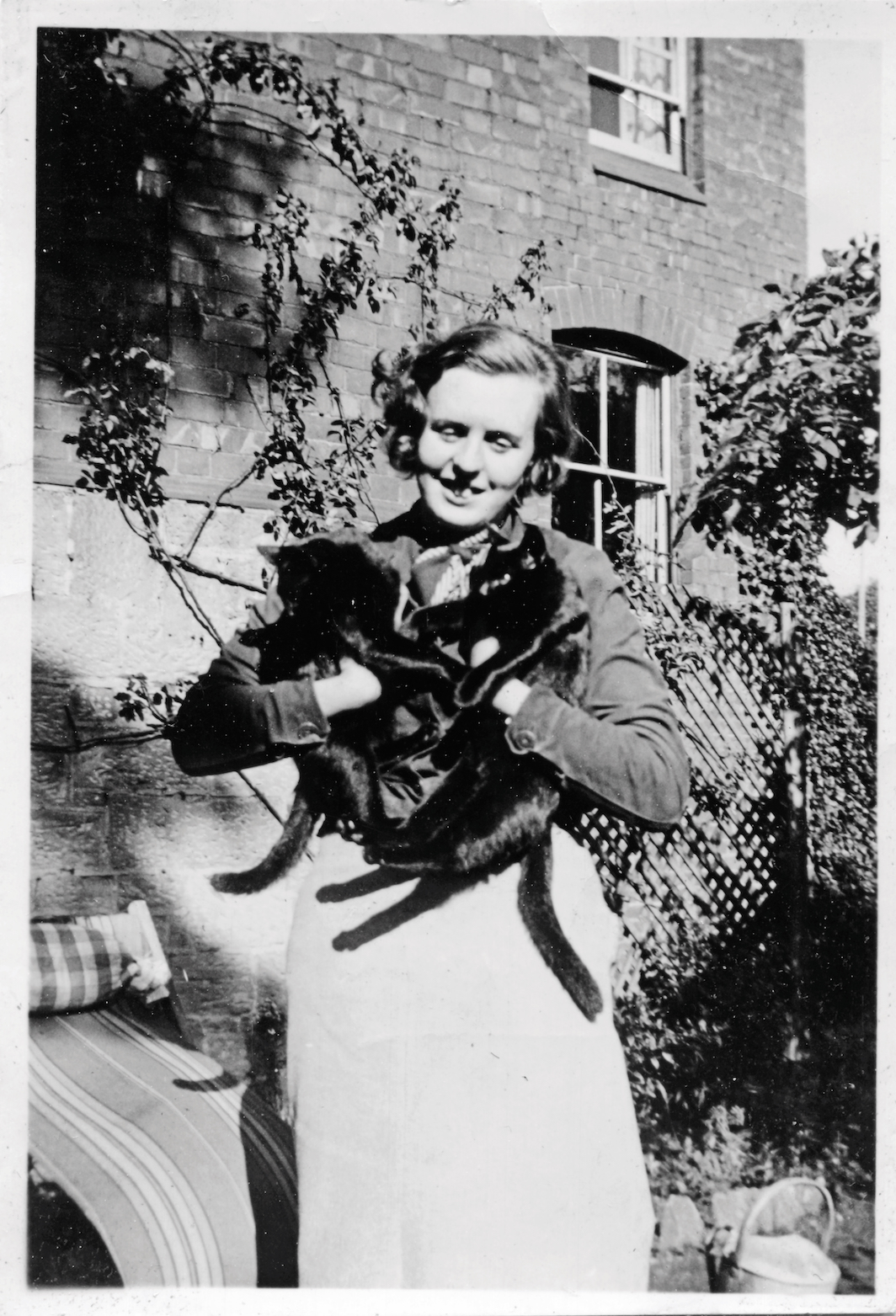

AT THE END of a long Michaelmas term working in the Barbara Pym archives in the Bodleian (how about that for an opening gambit?), I, six months pregnant with my second child, took a train out past Charlbury, caught a tiny bus, and deposited myself, thankfully in Wellington boots, on the side of the road near Finstock. I walked across two very muddy, December fields and found myself loitering outside of Holy Trinity, a mild, rundown, Victorian church. The church itself is a bit of a mishmash of Gothic Revival and practicality, with its 1905 chancel poking out awkwardly through its

TESSA HADLEY’S NEW NOVEL, Free Love, begins in 1967 London. The book is split between Otterley, a fictional suburb of manicured houses and back gardens, and Ladbroke Grove, the site of hippie excess, progressive dropping out, and émigré professional striving. Hadley focuses on Phyllis Fischer, a forty-year-old housewife, and her fifteen-year-old daughter Colette. The attention to these two characters, as they break slowly and then all at once from the circuits of the lives expected for them, makes up the bulk of the plot. Phyllis is elegant, the well-groomed and beautifully dressed mistress of a tidy and perfectly kept Arts

THE LIFE OF THE MIND, Christine Smallwood’s debut novel, begins with an ending. We meet Dorothy, a contingent faculty member in the English department where she used to be a doctoral student, as she negotiates the miscarriage of an accidental pregnancy. The pregnancy, at once unexpected and welcome, is a blighted ovum, “just tissue” according to her ob-gyn. The metaphor is clear: Dorothy’s academic career and the pregnancy are both projects of development and growth that never had a chance to thrive.

For every novel David Mitchell writes, two are published: there is the novel read by Mitchell’s fans, and the novel read by first-timers. Each of his books stands alone, as a thoughtful, researched, realistic portrayal of a specific time or place. There is a coming-of-age novel about a video-game obsessed adolescent in present-day Japan (Number9Dream), a novel about a Dutch visitor to a port near Nagasaki at the very end of the eighteenth century (The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet), a novel that deals with a widespread environmental collapse and the horror it brings to ill people (The Bone

HOW DO YOU WRITE A POLITICAL NOVEL IN 2020? How do you not write a political novel in 2020? It is impossible to imagine a contemporary writer presenting a version of the world that is not marked in some way by Trumpism, the threat of ecological catastrophe, the deepening gulf between the haves and the have-nots, the spectacle of racist police brutality. Yet the process of digesting the various horrors of the present into prose isn’t always noble. There is a way to use the novel as a balm to soothe the tempers of people who see themselves as opposed

In the title essay of her new collection, Rachel Cusk describes something she calls being sent to “Coventry.” This, as it is for many English families, is her family’s term for putting someone beyond the pale, for thrusting an offender out into silence. Her parents “send her to Coventry” when she does something they dislike, when she has slighted them or failed them in some way. “Sometimes,” Cusk writes,