Lisa Borst

ALEXANDER POPE, WROTE NICHOLSON BAKER in a roaming 1995 essay about allegorical uses of the word “lumber,” was “one of the most skilled word-pickers and word-packers in literary history.” Across three erotic novels, seven non-erotic novels, four nonfiction books, two essay collections, and one work of autocriticism about John Updike, Baker has proved himself to be among the great picker-packers too, especially in the fertile, anything-grows orchards of figurative language. Similes, analogies, metaphors, and euphemisms are Baker’s uncontested territory. Few areas of knowledge have evaded his encyclopedic curiosity, which means he can compare a piece of machinery to another piece of

THE DUBLIN-BORN NOVELIST PAUL MURRAY, who entered adulthood during Ireland’s rapid modernization in the 1990s, writes fiction about the problems that modernity everywhere has failed to solve. His characters come up against cruelty and abuse, inequality, grief, terrible loneliness, death—but generally their problems boil down to one of two sources, their families or their money. Murray’s 2010 boarding school–set bestseller, Skippy Dies—with its fucked-up children of sick or divorcing parents, its neatly bidirectional line between the traumas of childhood and the disappointments of adulthood—tilts toward the former, resulting in a warmly humane novel with an occasional YA-ish texture. In 2015,

ONE OF SAM LIPSYTE’S SIGNATURE ACCOMPLISHMENTS has been to find the baroque musicality in the emergent vocabularies—commercial, bureaucratic, wellness-industrial, pornographic—opened up by twenty-first-century English. “Hark would shepherd the sermon weirdward,” he writes in his 2019 novel about an entrepreneurial inspirational speaker, “the measured language fracturing, his docile flock of reasonable tips for better corporate living driven off the best practices cliff, the crowd in horrified witness.” Across his first six books, Lipsyte’s sentences have been excessive, pun-laden, and lyrically raunchy. When language threatens to sound measured, a character with a zany name can be counted on to fracture it.

Nell Zink. Photo: Francesca Torricelli Nell Zink lives in Brandenburg, Germany, but writes mostly about Americans and their countercultures and excesses. Her novels tend to be funny, immensely contemporary, and a little chaotic—in their careening prose style as well as in their joyfully unwieldy premises. She’s written about a group of anarchist squatters navigating real estate and movement strategy in Jersey City (Nicotine); a white lesbian who, having gone on the lam, successfully passes as Black in the woods of Tidewater, Virginia, where Zink grew up (Mislaid); and, most recently, a Lower East Side post-punk couple whose daughter stumps

Tamara Shopsin. © Michael Schmelling Although it sounds like the name of a sequel, LaserWriter II is the debut novel of writer and designer Tamara Shopsin; it takes its name from a laser printer manufactured by Apple in the early 1990s. The mechanics of printing are a formal concern throughout the book, which is divided by surprising page breaks and pixelated illustrations, as well its central plot fixture: Shopsin follows Claire, a young New Yorker with anarchist leanings, through her stint as a printer technician at Tekserve, a computer-repair shop that operated on West 23rd Street until 2016. Between

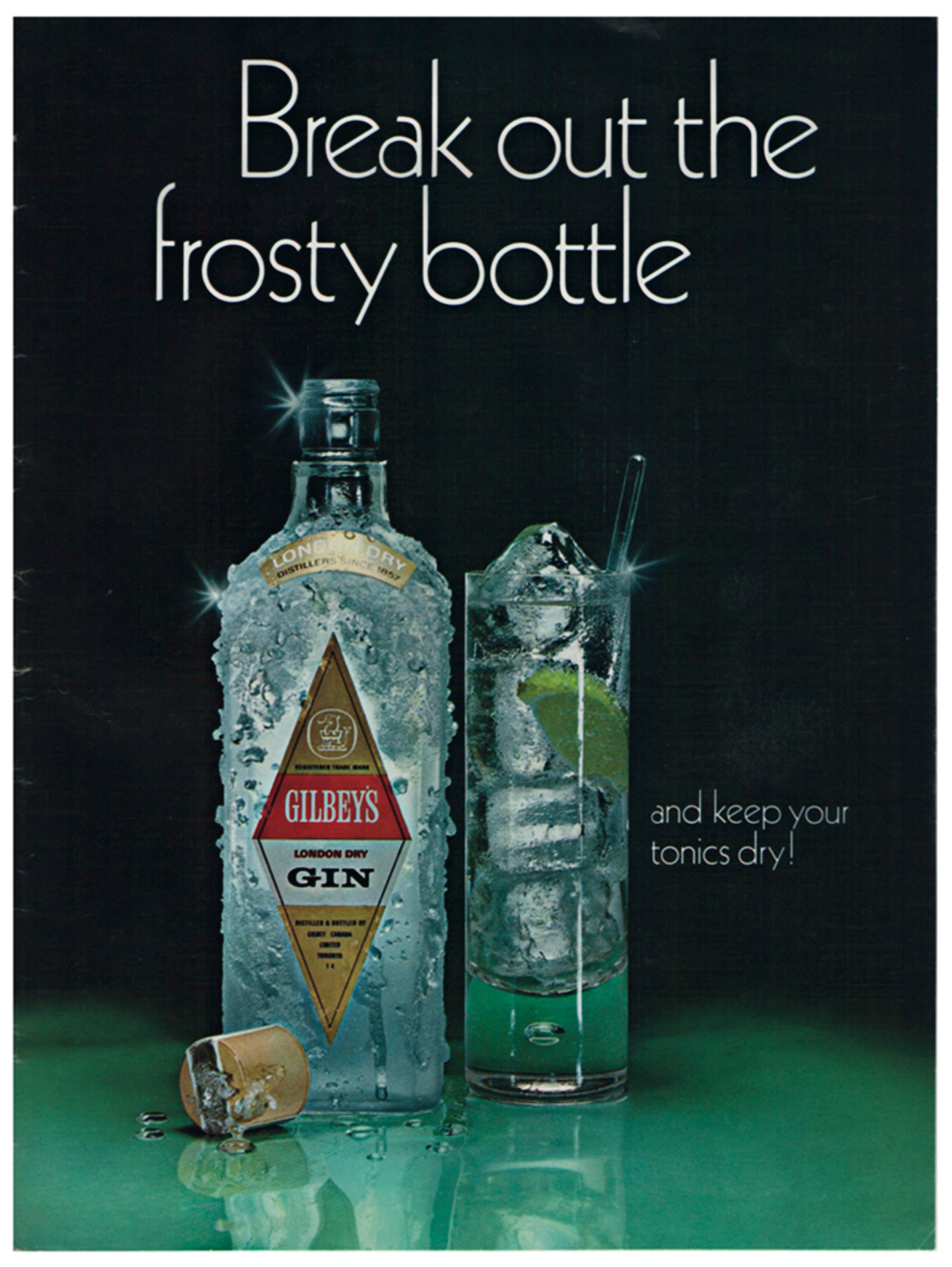

“AT THIS POINT, you probably should take several deep breaths in order to relax, there is much more to come, if you’ll pardon the expression,” cautions Wilson Bryan Key, in the first chapter of his 1973 pulp best-seller Subliminal Seduction. The book, which ignited one of the Cold War era’s more banal panics—that the advertising industry is a black site of veiled salacious messages—is best remembered for its analysis of an ad for Gilbey’s gin, which Key claimed contained the letters S-E-X embedded in ice cubes. But Key goes on to argue that television and magazine ads contained stronger stuff