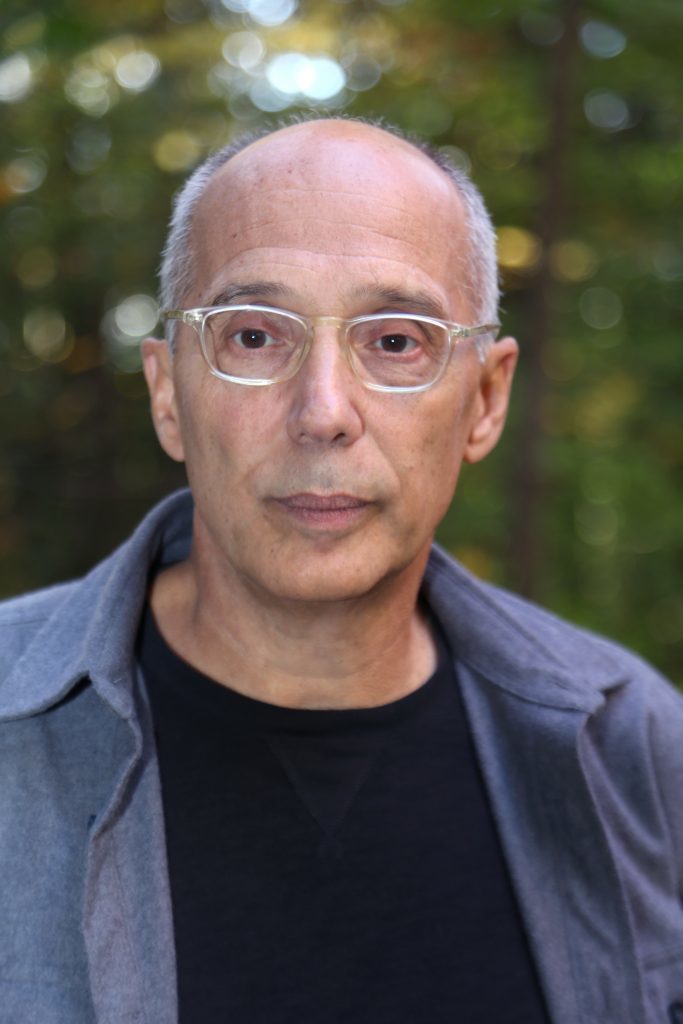

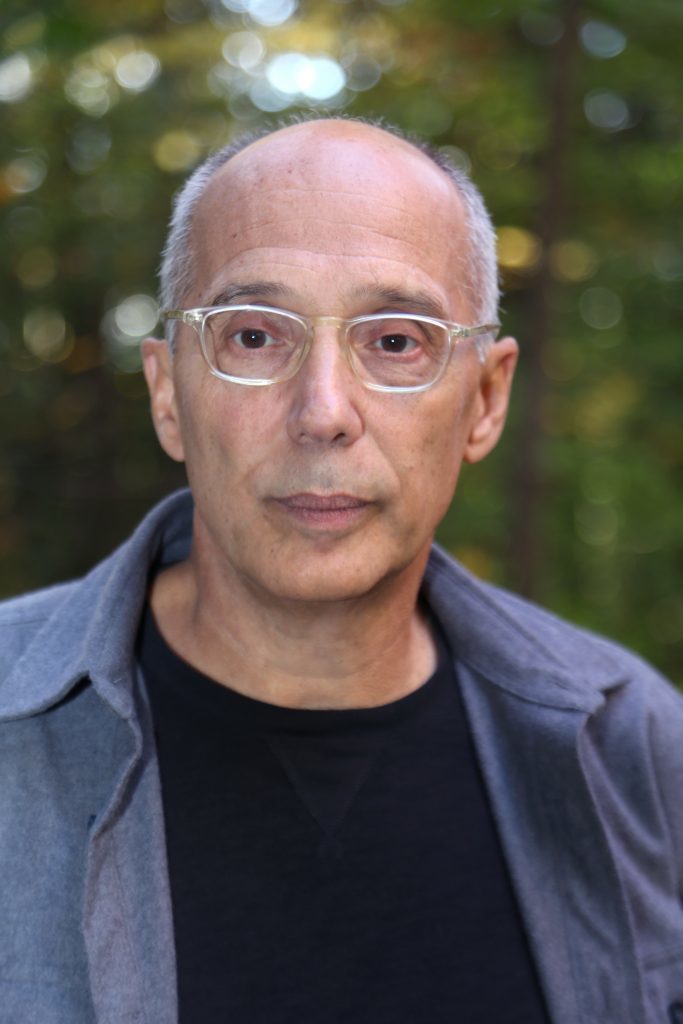

Louis Bury

Albert Mobilio From the story of a race with no finish line to the story of a hunt for a used slipper, the mischievous, ludic distortions of Albert Mobilio’s Games Stunts are like images in a funhouse mirror reflecting both gaming culture and culture at large. “This is the way of the world,” squawks one narrator, parroting a shopworn mantra whose Trumpian tang tastes extra bitter these days, “all against all, winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” But Mobilio’s sardonic literary gloss on competition defies Manichean simplicities. You can’t easily win a race when there’s no finish line. The rubric “conceptual poetry” encompasses works written using a variety of techniques: sampling, appropriation, documentation, and constraint, among others. By far the most prominent—and controversial—is appropriation: A work such as Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day (2003), a word-for-word transcription of one day’s New York Times, extends Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made practice into the literary realm. In the 2004 essay “Being Boring,” Goldsmith writes, “You really don’t need to read my books to get the idea of what they’re like; you just need to know the general concept.” This coy sentiment, delivered in a deadpan voice, suggests an advantage to a conceptual-poetry syllabus: You