Melissa Febos

There is a conventional wisdom about memoir that claims a writer must have sufficient hindsight in order to write meaningfully about her past. This has not been my experience. All that has been required of me to write about something is this change of heart. A shift toward, or away, or perhaps a desire to return to some truer version of myself. I don’t even have to know that I’ve made it, but when I look back at the beginnings of everything I’ve ever written, there it is.

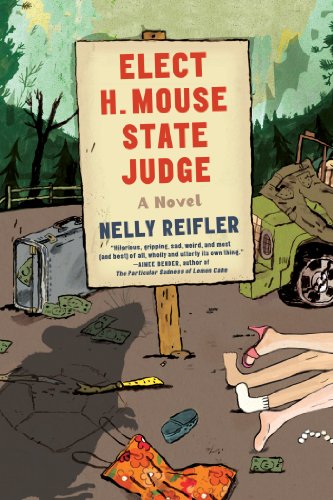

In Nelly Reifler’s new novel, we’re introduced to a diminutive protagonist with a good heart and a robust furry belly. A widower, and, yes, a mouse, H. Mouse loves his two daughters, Susie and Margo, with a profound and sometimes melancholy adoration. His campaign for State Judge, based on his generous philosophy that “we are, each of us, born in a state of grace and innocence,” has strong public support. In darker moments, though, when his past slips out from the shadows, it is hard for H to include himself in his belief “that no matter what someone may do, By marrying the intimacy of autobiography with the aesthetic eclecticism of the graphic novel, graphic memoirs occupy the fertile realm between fiction and nonfiction, as well as between literature and art. I first encountered this narrative chimera in the 1990s, when I read Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World, and the feminist zines I found along the windowsills of Boston’s indie bookstores. This underground aesthetic seemed to depict my own disaffected experience and burgeoning politics; since then, I’ve been glad to see long-form graphic storytelling find a larger audience. The following volumes are a small sampling of a rich genre. One Hundred