IN THE WORK of the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, the shortest distances are often also the greatest: The space between self and other can be maddeningly difficult to traverse. Full of magical transformations, ritual sacrifices, and turbulent prophetic dreams, Cortázar’s writing abounds with troubled pairings, unlikely and uneasy doppelgängers who come apart even as—especially as—they converge. In one of his stories, “The Distances,” a wealthy Argentine woman dreams repeatedly of a Hungarian peasant. When she finally encounters the object of her visions on a bridge in Budapest, she embraces the woman and watches, helpless, as her double walks off in her body. The image is one of distance bound up in proximity: the exchange is a “total fusion” that is, in the end, as much of an estrangement as it is an embrace. In another story, “Axolotl,” a man who feels a mysterious affinity with the axolotls in an aquarium is transformed into one of their number. His former human self, he reports, is “more than ever one with the mystery that [is] claiming him.”

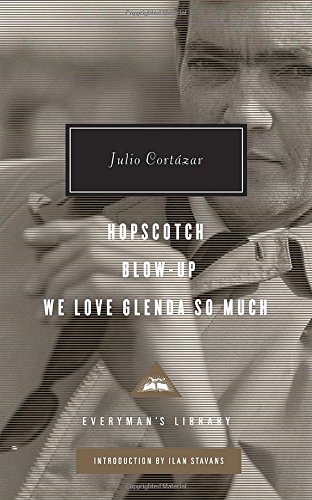

Both of these tales, along with Cortázar’s landmark “counter-novel,” Hopscotch, appear in the new Everyman’s Library anthology of his writings. This splendid collection, assembled in honor of the centennial of Cortázar’s birth, also contains Blow-Up and Other Stories and We Love Glenda So Much and Other Tales. Hopscotch, a sprawling experiment in nonlinear narrative, takes up well over half the volume: The novel consists of 155 chapters, many of which, as Cortázar writes in his preliminary “Table of Instructions,” can be read and re-read in any order. The first through the fifty-sixth are to be read straightforwardly; the order of the rest, which wind their way backwards and forwards, is up to Cortázar’s readership.

Reading Hopscotch—reading Cortázar—is a bit like navigating a labyrinth. Behind each corner, each chapter doubling back on itself, lurks the prospect of an unforeseen encounter, at once disturbing and tantalizing. Distances are distorted. Ostensible shortcuts will lead you on a scenic route that provides alternate, unexpected perspectives. All the while, Cortázar’s work invokes a sort of Zeno’s Paradox: The closer we come to the objects of our fear or fascination or love, the farther away we find ourselves.

Often described in the first person, Cortázar’s uncanny metamorphoses—man into axolotl, axolotl into man, one being into the wholly alien experience of another—function as a sort of distancing. As the man-turned-salamander in “Axolotl” gazes at his former self through the glass of his new aquarium, he reflects that “the bridges were broken between him and me, because what was once his obsession is now an axolotl, alien to his human life.” And yet Cortázar suggests that it is precisely in this strangeness that familiarity consists:

The anthropomorphic features of a monkey reveal the reverse of what most people believe, the distance that is traveled from them to us. The lack of similarity between axolotls and human beings proved to me that my recognition was valid, that I was not propping myself up with easy analogies…. They were not human beings, but I had found in no animal such a profound relation with myself.

Over this handsome, marmoreal Everyman’s Library volume hovers the specter of the axolotl, a “diaphanous interior mystery” that jolts us out of ourselves and exposes us to an experience that is beguilingly, brutally other.

CORTÀZAR WAS displaced from the moment of his birth. The son of an Argentine diplomat, he was born in Brussels in 1914; five years later, his family was obliged by the German occupation to relocate to Banfield, a suburb of Buenos Aires. Cortázar’s father left shortly thereafter, leaving Cortázar to be raised by his mother, a woman of German and French descent.

As an adult, Cortázar embraced his multinational origins, working first as a translator and then, briefly, as a professor of French literature at the University of Cuyo in Mendoza. In 1951 he fled to Paris, where he would remain for the rest of his life, save for short trips and vacations. Though his exodus represented an earnest attempt to thumb his nose at the Péron regime, it was not until 1973, with the publication of his controversial political novel, A Manual for Manuel, that he was officially exiled by the Argentine junta. In 1951 he was still a relatively obscure figure, an aspiring author with only a handful of publications to his name.

Cortázar’s second collection of stories, End of the Game, was published in 1956, after he had been abroad for five years. A third collection, Secret Weapons, followed in 1958, and Hopscotch, which is set mostly in Paris, came out in 1963. As Cortázar gained literary renown, he became more vocal in his opposition to the corruption and brutality that characterized South American politics. When he was awarded the prestigious Prix Médicis in 1974, he donated his winnings to political prisoners in South America, and the next year he wrote a witty comic book-cum-political-commentary called Fantomas Versus the Multinational Vampires: An Attainable Utopia, in which an animated Susan Sontag and Octavio Paz make memorable if stylized appearances as they fight alongside comic book superhero Fantomas to overthrow multinational corporations. When Cortázar died of cancer in 1984, he was perhaps better recognized as an activist than a writer. His later works were tainted by what many regarded as unsuccessful forays into political critique—a betrayal of his earlier, more aesthetically motivated writing.

Although Cortázar was in some senses an international writer, fully at home in neither his native Argentina nor his adoptive France, he was also decidedly Argentine. He lived in Paris but wrote in Spanish, and his first published story, “House Taken Over,” was printed in 1946 in Los Anales de Buenos Aires, an eminent Argentine literary journal edited by none other than Jorge Luis Borges. He was heavily influenced by Poe, whose works he translated into Spanish—but even his internationalism harkens back to Borges, the Argentine master, who was known for championing a global approach. Argentine tradition, Borges proclaimed in 1951, is “the whole of Western culture”: “The nationalists pretend to venerate the capacities of the Argentine mind but wish to limit the poetic exercise of that mind to a few humble local themes, as if we Argentines could only speak of neighborhoods and ranches and not of the universe.” Argentina, Borges went on to argue, is of a cultural piece with Europe and America, but it is also divorced from them. Argentine writers therefore enjoy a unique sort of freedom, one that allows them to invoke European or American literary precedent—or to upend it. Borges’s own work—national literature that draws on multinational resources—unforgettably illustrated his point.

Following Borges’s elegant injunction to set aside nationalistic proprieties and “lose ourselves in the voluntary dream called artistic creation,” Cortázar wrote dark surreal stories, more nightmare than dream. “House Taken Over” describes a brother and sister driven out of their home by “them,” an unseen force that gains control of the house room by room. The protagonists’ gradual, unwilling exodus is not unlike their creator’s: Much like Cortázar, a fluent French speaker and near life-long resident of Paris, the characters in “House Taken Over” stubbornly cling to what’s left of their origins.

And indeed it was Cortázar, long-time ex-patriot and eventual French citizen, who headed El Boom, an eruption of South American literary activity that took as its subjects neighborhoods, ranches, and the universe. Magical realists such as the Columbian Gabriel García Marquez integrated the prosaic and the supernatural, anticipating the work of later authors like Roberto Bolaño and César Aira. Cortázar, who wrote earlier than most of the other Boomers, served as their inspiration and model.

Yet Cortázar, an eternal outsider in his various domiciles, felt distanced from the movement he had set into motion. Where Marquez’s and Isabel Allende’s writing emphasized the sunny magic of everyday discovery, a sort of antidote to the pervasive political violence they faced in their daily lives, Cortázar’s highlights the essential strangeness that renders banalities alien, even monstrous. Like the eyes of the axolotl, Cortázar’s stories speak to us “of the presence of a different life, of another way of seeing.” There is, the man-turned-axolotl observes, “a terrifying purity” about the axolotl’s gaze.

BY CORTÀZAR’S OWN lights, Hopscotch was one of his greatest achievements. A choose-your-own-adventure book for adults—or precocious, postmodernist children—the book is divided into three sections, “From the Other Side, “From This Side,” and “From Diverse Sides.” The first reading—the only one with any pretension to linearity—begins with “From the Other Side” and ends with “From This Side.” The second reading, which weaves its way through the pastiche of newspaper clippings, quotations, musings, and anecdotes that makes up the “Diverse Sides” chapter, never really ends: After a five-hundred-page journey spanning almost the entire text, we move from chapter 58 to chapter 131, which in turn instructs us to return to chapter 58, which in turn instructs us to return to chapter 131, and so on and on.

At its core, Hopscotch is a love story. In all its iterations, the book hinges on the relationship between Horacio Oliveira, an Argentine expatriate, and his enigmatic, Uruguayan lover La Maga, “the magician.” Though its plot is mutable, Hopscotch “begins” in Paris and “ends” in Buenos Aires. “From the Other Side,” the Parisian portion, follows Oliveira, La Maga, and their band of impoverished Bohemian friends, the self-proclaimed “Serpent Club.” Oliveira and La Maga have an unconventional romance, founded on their practiced commitment to non-commitment. They never arrange dates in advance, preferring to wander the city in hopes of a chance meeting. The “first” chapter of Hopscotch begins with a question: “Would I find La Maga?”

Oliveira is obsessed with uncovering a “center,” an incontrovertible source of meaning likened throughout the book to the winning square in a game of hopscotch. Yet he finds himself over-intellectualizing what the uneducated yet intuitive La Maga grasps effortlessly. Lacking a destination to guide his aimless meandering, patronizingly dismissive of La Maga’s insights, Oliveira drinks, waxes philosophical, and chases after other women. The section comes to a head when La Maga’s infant son dies at a Serpent Club party. The end of “From the Other Side” sees a traumatized La Maga disappear, leaving Oliveira bereft.

In “On This Side,” Oliveira returns to Buenos Aires, where he is reunited with his best friend, a man called Traveler although he has never travelled. Traveler’s wife, Talita, reminds Oliveira of La Maga, and tensions run high as Talita and Oliveira battle their growing attraction to one another. In one passage, the friends construct a bridge between their respective apartments, stretching wooden planks across the street from one set of windows to another. The mood is initially cheerful, but as Talita sits suspended on the planks, wavering, unsure whether to move forwards towards Oliveira’s apartment or backwards towards her husband, the tone shifts, and the scene escalates into a quiet crisis.

The second reading introduces a new character, Morelli, an author and the darling of the Serpent Club. Morelli is tangential to the plot, but he turns up every so often to offer thinly veiled commentary on Hopscotch’s structure. Of Morelli’s novel-in-progress, Cortázar writes:

Morelli tried to justify his narrative incoherencies, maintaining that the life of others, such as it comes to us in so-called reality, is not a movie but still photography, that is to say, that we cannot grasp the action, only a few of its eleatically recorded fragments….

When members of the Serpent Club worry that Morelli’s publisher will botch the ordering of his novel’s chapters, Morelli replies that the book will turn out “perfect” precisely when his readers jumble it.

The first book contained within Hopscotch ends on a dramatic note: Oliveira commits suicide by throwing himself out the window of a mental hospital, landing in a hopscotch board chalked onto the pavement. The second book has no decisive ending: We shuffle back and forth between chapters 58 and 131. In neither of these prescribed readings does Oliveira succeed in escaping the web of artifice and over-theorization that entraps him from the start. In the first, he returns directly to the game, with all its stifling rules and complications. In the second, he remains enmeshed in a circular conversation—within the confines of the book, a different kind of “hopscotch.” In both cases, La Maga’s simple, joyful transcendence eludes him: She alone has managed to exit the novel entirely. It is no coincidence that to win a game of hopscotch is also to end it. In the case of this Hopscotch, at least for Oliveira, there is no end, and no winning.

LIKE OLIVEIRA IN search of La Maga, Hopscotch proposes a quest that defines its object, not the static and uncomplicated relationship of lover to a beloved or a traveler to a clear destination but the fraught relationship of an artist to his creation—a traveler who generates his destination via the act of traveling, a lover who manufactures his desire in the spaces between self and other. For Cortázar, in Hopscotch more than ever, the distance between origin and endpoint is not a means to an end but rather an end in itself. To read Hopscotch is therefore to invent it, for hopscotch is a game—an interactive activity that invites, even requires, our participation. (“For me, literature is a form of play,” Cortázar said in an interview in the Paris Review. “But I’ve always added that there are two forms of play: football, for example, which is basically a game, and then games that are very profound and serious.”)

Hopscotch is ambitious, maybe visionary, but it doesn’t quite come off. Set in what seems like a perpetually rainy Paris, the perfect place for Oliveira to cultivate his bleak, fungal malaise, the novel recalls Henry Miller in its glorification of a particularly self-indulgent brand of Parisian disorder. With his jazz, his soggy cigarettes, his incessant womanizing, and his unassailable sense of self-importance, Olivera is all too recognizable. We can picture him in some filthy garret, poorly shaven, planning his next sexual conquest, thinking what he deems Big Thoughts, Appreciating Jazz, issuing laughable pronouncements like “only by living absurdly is it possible to break out of this infinite absurdity.” Oliveira wallows in a bog of self-pity, and for all its formal innovation, Hopscotch suffers for its indulgence of the man. The work is original but cumbersome: The finished product does not live up to its own structural promise.

In delightful contrast, Cortázar’s stories are tightly—beautifully—contained. In “Letter to a Young Lady in Paris,” the narrator writes: “It offends me to intrude on a compact order…. It hurts me to come into an ambience where someone who lives beautifully has arranged everything like a visible affirmation of her soul.” He may as well have been speaking of the elegant concision of the story he inhabits.

In “Bestiary,” one of Cortázar’s masterpieces, a child vacations on an aunt’s country estate, where a tiger roams the premises unrestrained. The setting is refined, idyllic, even aristocratic, but the tiger, whose presence is never explained, upsets the pastoral order. Tensions between the adults undergird the story, which is told from the naive yet discerning perspective of the childish visitor. Little is articulated, and yet the silences are pointed: Quivering beneath the polite, bourgeois artifice of pleasantries and platitudes is a massive and horrible violence, a household haunted by a fury that we, like the childish narrator, can sense but cannot explain.

Against the backdrop of Cortázar’s controlled prose, the smallest gestures are amplified. Even when Cortázar forgoes his usual surrealism, he remains masterfully attentive to detail. In “Graffiti,” a graffiti artist protests a totalitarian regime’s strictly enforced prohibition on street art by setting out each night to decorate the city. Soon he finds himself in dialogue with another artist, who “answers” his pieces with drawings of her own. “So many things begin and perhaps end as a game,” the story begins falteringly. Though the artist has never laid eyes on his counterpart, he begins to fall in love with her. He sees her for the first time only when she is violently arrested mid-drawing, leaving behind a “figure, a circle or maybe a spiral, a form full and beautiful, something like a yes or an always or a now.” It is a lovely and sad story—simple, subtle, kind.

If the games in Hopscotch are adversarial, more artificial entanglements than collaborative exchanges, the game in “Graffiti” is an exercise in intimacy. The story puts two artists into conversation with each other, structuring and facilitating their romance, transforming their emotion into something more intelligible without undercutting its force. Here, the distances that Cortázar so often invokes shrink. Cortázar’s games are the serious kind, the kind that force us to reckon with each other. His writing is a merciful solution to the problems it poses, offering a way out of the eternal hopscotch, demonstrating, at its best and most human moments, that the obstacles to contact are not so insurmountable after all. And these moments, even in the writer’s most realist stories, come with their own sort of magic.

Becca Rothfeld writes about books, art, and culture, often for Hyperallergic.