In the late nineteenth century, Louis Pasteur’s laboratory assistants made sure to always have a loaded gun on hand. Their boss, who was already famous for his revolutionary work on food safety, had turned his attention to rabies. Since the infectious agent—later identified as a virus—was too small to be isolated at the time, the only way to study the disease was to keep a steady of supply of infected animals in the basement of the Parisian lab. As part of their research, Pasteur and his assistants routinely pinned down rabid dogs and collected vials of their foamy saliva. The risk of losing control of these animals loomed large, but the bullets in the revolver weren’t intended for the dogs. Rather, if one of the assistants was bitten, his colleagues were under orders to shoot him in the head.

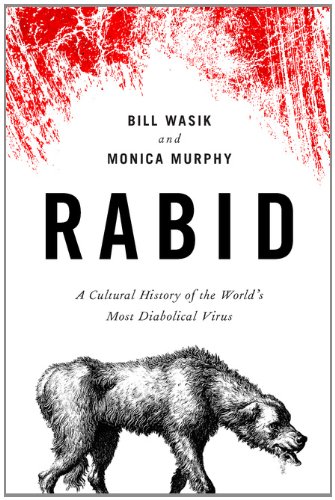

As Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy document in their new book Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus, the horror of rabies has been with us since the beginning of human civilization. Rabies is the dark side of domestication, always potentially lurking behind the eyes of the animals that live beside us. Transmitted through a bite, rabies releases the monster within the animal and the animal within the human, causing feverish hallucinations, involuntary orgasms, an intensely physical revulsion to water, and, before Pasteur developed his vaccine, an excruciating, inevitable death. Notwithstanding its 100 percent fatality rate, Wasik and Murphy argue that rabies is uniquely terrifying because it “challenges the boundary of humanity itself.”

Today we know that many of our most feared diseases originated in animals and made the jump to humans—think AIDS, Ebola, and avian and swine flu, to name a few—but until germ theory was developed in the nineteenth century and refined in the twentieth, rabies was the only obvious instance of animals making humans sick. That it was often dogs doing the infecting only added to the disease’s mythological power. Dogs may have co-evolved with humans, but a part of them remains beyond our control and comprehension—a fact that was especially obvious during ancient times and the Middle Ages, when people frequently had occasion to see healthy, friendly dogs casually eating human corpses. This tension, which Wasik and Murphy dub the “dual nature of the dog” contributed to the unsettling sense that the beloved pet could at any moment succumb to the wildness within.

Rabies has always been as much metaphor as disease, making it an excellent subject for cultural history. The first half of Rabid chronicles how the virus contributed to and played upon our fears of animalistic possession and monstrous transformation. This account begins in ancient Mesopotamia, traverses the nineteenth century, and culminates, perhaps unavoidably, in a contemporary discussion of werewolves and vampires. While interesting, this section is hampered by the fact that until Pasteur made effective prevention possible, the human relationship to rabies remained largely unchanged. It is not until we meet “King Louis” and his twentieth and twenty-first century heirs that the book finds its heroes: the scientists who have looked “the devil in the eye” and figured out how to stop it.

Murphy is a veterinarian and Wasik is a senior editor at Wired (where, full disclosure, I recently became an editorial fellow), so it is no surprise that they are at their best when writing about the details of experimental science. The chapter on the creation of the rabies vaccine, in particular, veers enthusiastically towards the gritty, recounting how years of grisly experiments on the brains of living animals culminated in the first public test of the vaccine on a nine-year-old boy. It was one of the first instances of a medical breakthrough born of laboratory science, and it was a supremely effective publicity stunt in the name of public health.

Over one-hundred years after Pasteur unveiled his vaccine, rabies can still only be prevented, not cured. It now falls into the troubling category of neglected diseases, since it doesn’t kill enough people in wealthy countries to attract the funding necessary to prevent the tens of thousands of deaths it causes every year in the developing world. At the moment, the most effective way to stop the virus also happens to be the cheapest: vaccinate dogs before they are exposed. But as Wasik and Murphy find when they visit Bali, which reacted to the virus’s arrival in 2008 by encouraging citizens to kill stray dogs, the visceral fear of rabies often overrides logic and political will.

Unlike in Bali, rabies is now nearly invisible in the US. We live comfortably in our skyscrapers and manicured parks, “naming our cul-de-sacs for whatever wilderness we dozed to pave them,” until rabid raccoons are discovered in Central Park, or a graphic story surfaces about what it takes to fight off a rabid animal (hint: it involves beating it to death with a tire iron) and the horror comes roaring back. Rabies has always been the price of living in a world we can’t ever fully tame. As Wasik and Murphy write of the disease, “It’s gone until it isn’t.”

Lizzie Wade writes about science and culture in California. She is currently an editorial fellow at Wired.