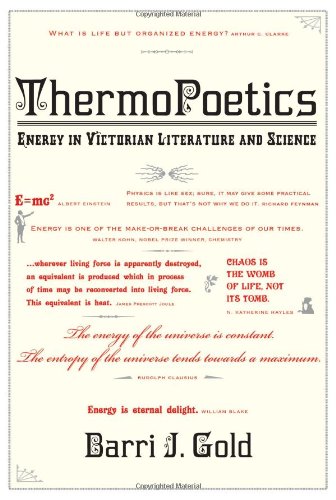

While it is widely accepted that science influences literature, it is a much dicier proposition to suggest that literature influences the sciences. Even physicists, who frequently declare their equations as beautiful as poetry, are rarely willing to cop to being culture-bound. According to English professor Barri J. Gold, however, physics—and nineteenth-century physics in particular—is heavily indebted to literature, and vice versa. In ThermoPoetics: Energy in Victorian Literature and Science, Gold argues that some of the universal truths that eventually ended up codified as “the laws of thermodynamics” were presaged by poets and other writers, and that the conversation swirling around their work played a vital role in legitimizing the emerging field and turning even its most troubling hypotheses into facts.

After centuries of flying under the cultural radar, science exploded into the popular consciousness in the nineteenth century. As the Industrial Revolution and its attendant technologies—the commercial steam engine, the telegraph, the radio, and electric power, just to name a few—forever changed how Europeans lived and worked, science went from being a hobby practiced by wealthy amateurs to a driving social and economic force. Not coincidentally, as applied physics was changing the daily lives of millions of people, other branches of science, such as evolutionary biology, were calling attention to the fundamental instability of our universe, our planet, and our species. But as Gold points out in ThermoPoetics, there was another scientific field that was equally bound up in Victorian cultural anxieties about change, loss, and transformation: thermodynamics. In her first example of what she calls “thermopoetics”—a flexible term that encapsulates concrete examples of influence between Victorian energy science and literature as well as more ephemeral parallels—Gold explores how poets and physicists alike dealt with the anxiety of inevitable loss, or, in thermodynamic terms, entropy.

Gold’s main literary example is In Memoriam, a long and powerful elegy written by Alfred Lord Tennyson. In coping with the death of his friend Arthur Henry Hallam, Gold argues that Tennyson dealt with his grief by reconfiguring loss as change: “What are thou then? I cannot guess; / But tho’ I seem in star and flower / To feel thee some diffusive power, / I do not therefore love thee less.” Since “transformation without loss”—which physicists would eventually call the conservation of energy—was not yet articulated as a thermodynamic principle when the poem was published in 1851, Gold argues that Tennyson was among the first to introduce the idea into popular culture.

With In Memoriam in mind, Gold turns to the early energy scientists and sees them grappling with similar anxieties—and reaching similar conclusions—about loss and change after Tennyson’s poem was published. James Prescott Joule, for example, was devoted to the theory of energy conservation decades before it was formally codified as a law of physics. His certainty was not based on experimental evidence, but on the conviction that only God had the power to create and destroy. He explained away troubling evidence in his experiments, where he saw evidence of energy being lost and gained, by proposing that energy was never truly lost, but rather transformed into heat.

Gold is not arguing that Tennyson’s poem directly influenced Joule or any other Victorian energy scientist, but rather that literature helped shape the cultural conversation around the new field. It is conceivable, she says, that a widely-read poem like In Memoriam could have primed the Victorian public to accept the “interplay between conservation and dissipation” that drove the development of energy science in the second half of the nineteenth century, or even helped physicists themselves approach “the imponderables” of heat, energy, and force.

At the very least, Gold makes a convincing case that the boundaries between physics and literature were not quite as clear-cut for the Victorians as they seem to us today. James Clerk Maxwell alone provides her with a font of material; not only does he quote In Memoriam in a letter, but he wrote his own poetry arguing in favor of mathematical abstraction in physics and exploring the “likeness of light and water”—the “fluid analogy” that would later inspire his equations uniting electricity, magnetism, and light.

As thermodynamics grew more established, its language began making its way into social treatises, science fiction, and popular novels. In a playful tone, Gold considers the imperial consequences of thermodynamics in the Victorian sci-fi novel, The Coming Race, reads Bleak House as a treatise on engine design, and in Dracula detects shades of chaos theory, radioactivity, and other twentieth-century scientific developments that would eventually support the laws of thermodynamics.

With section headings like “Entropy: This Time It’s Personal,” Gold’s tone can sometimes seem too arch, but her determination to write an accessible academic book is admirable. Winding sentences and impenetrable vocabulary aren’t the only reasons that many academic books are not well-suited to pleasure reading, however, and Gold doesn’t go far enough in jettisoning other scholarly conventions. For example, there are no overviews of the plots, characters, and themes of the books discussed, making it difficult for the casual reader to follow Gold’s arguments about these texts.

Ultimately, the most impressive thing about ThermoPoetics is not its arguments—which often can’t claw their way out of the quicksand of literary theory—but rather its interdisciplinary premise: Gold brings literary criticism, science studies, and physics into a true conversation. While some of her conclusions fall a bit short, her approach offers a new way of thinking about the relationship between physics and poetry that is based not on direct, verifiable influence, but on a sort of ambient cross-pollination, one which helps all kinds of creativity thrive.

Lizzie Wade writes about science and culture in California. She is currently an editorial fellow at Wired.