Clothes are often written off as a waste of time and energy, something to distract us from what really matters. Yet you have to get dressed—or you do if you want to leave the house. In this way, the question of what to wear—of what your clothing choices express to the world, and what they mean to you—is a fundamental one. And the clothes you pick unavoidably reveal the values and priorities of a given moment, as Emily Spivack has emphasized on her blog for the Smithsonian Museum, Threaded, where she writes about the historical significance of stockings and sequins, dinner jackets and tartans. In 2010, Spivack started Worn Stories, a website that collects photos of clothing along with short narratives describing the reasons they matter to the wearer. Spivack is interested in the combination of cloth and body, the way a material object becomes a physical extension of a person, or the material embodiment of one’s personality. Her new book, Worn Stories, is a more fully realized version of the original project: a collection of personal stories that treats clothing as vital instead of disposable.

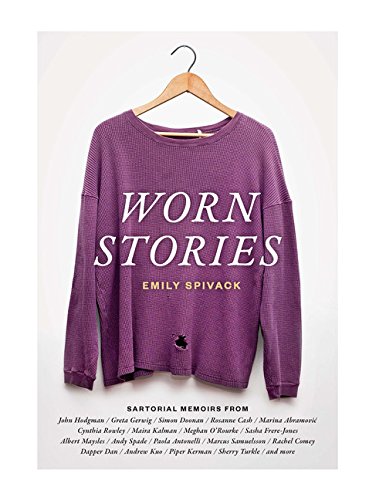

The blog offered a standard submission form for anyone who wanted to send a story and a photo. The result was an incredible assortment of characters and costumes: brides and prom queens, basketball jerseys and band t-shirts. The clothing was sometimes seen on the storyteller, sometimes displayed in a closet, or held aloft by two disembodied hands. The book takes a more uniform approach, showing each item in front of a white backdrop. The design mimics traditional fashion editorials in mainstream magazines, in a work that effectively removes fashion from the discussion.

That’s the challenge Spivack has taken on: to convince readers that clothing and fashion are separate realms. Clothes are what we wear; fashion is the industry that sells them. Clothes are personal; fashion is commercial. The distinction is crucial. Spivack says she is neither “overly sentimental” nor “a hoarder.” Yet the sentimentality of both the book and the blog is exactly their virtue. Ross Intelisano, a lawyer, writes about losing a collection of handmade silk ties inherited from his grandmother. Dorothy Finger recounts her time hiding from Nazis in a forest outside of the Ukraine; when she returned, the only survivor, to the department store her family had owned, all that was left was some brown fabric, which she made into a suit. There are stories about clothes never worn, like one from James Johnson III, a man who specially commissioned a traditional beaded Native vest for his wedding and then left it behind in a garment bag. And there are stories from people we never thought to picture, like Susan Bennett, the original US voice of Siri on the iPhone, who describes a jacket she wore while touring as a backup singer.

Some contributors—including Simon Doonan, Sasha Frere-Jones, and Greta Gerwig—narrate their stories to Spivack. Others—David Carr, Piper Kerman, Maira Kalman—write their own. The length of the accounts varies; the contributors’ honesty remains consistent.

Notably, there aren’t any photos of people. The implication is that it isn’t necessary to show them—their bodies are not what give their clothes meaning, their words do. It’s hard for me to explain, for example, how it felt to lose a friend at seventeen, or to meet my partner, or to quit a job I loved. It’s easier, and in a way more poignant, to describe the black A-line skirt that’s been collecting dust in the back of my closet since the funeral, the jeans I wore on our first date, the feeling of a wool sweater as I pressed my back against a chair. The evidence of the wearer is in the worn: in the stuff that is frayed, soft, used until the clothes become the stories themselves.

Haley Mlotek is the editor of The Hairpin and the publisher of WORN Fashion Journal (no relation to the book under review). She lives in Toronto.