IN AUGUST 1969, the Billboard “Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles” chart was rechristened “Best Selling Soul Singles.” A new type of music had emerged, “the most meaningful development within the broad mass music market within the last decade,” according to the magazine. The genre mystified much of the mainstream press. Publications like Time announced soul music’s birth one year earlier as if it were a phenomenon worthy of both awe and condescension. Its June 1968 issue featured Aretha Franklin as its cover star and called the music “a homely distillation of everybody’s daily portion of pain and joy.” Franklin was

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

WHILE THE BALKANS are generally not known for neighborliness, that reputation is still quite recent. Most would date it to the mid-nineteenth century, when the rise of the nation-state suddenly spurred competition over inheritances that had traditionally been shared. The term “Balkanization”—which crystallized the peninsula’s characterization as bitterly divided—was coined by the New York Times only in 1918, in the wake of the Balkan wars, when the ousting of the Ottomans sparked a land grab among the kingdoms of the former Balkan League. If anything, the previous centuries of occupying empires—from Illyrians and Thracians to Byzantines and Bulgarians—had imparted a

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

As its title suggests, Wagnerism is not precisely a book about Richard Wagner, or even about his music. It is rather, as Alex Ross clarifies, “about a musician’s influence on non-musicians”—a narrow premise seemingly for a work of more than seven hundred pages, but Ross is only teasing out the most salient points from a crowded and mesmerizing history. His book stretches from the opening of Wagner’s first mature operas in the 1840s to the present moment, when fantasy movies and comic books teem with Wagnerian echoes, and the operas themselves are accessible in multiple formats on a previously unimaginable

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

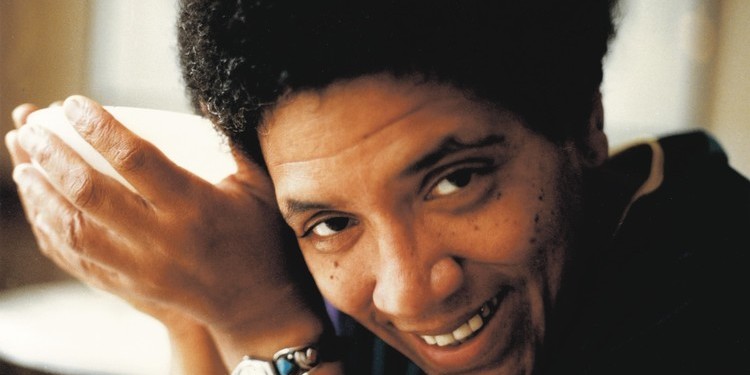

ONE APRIL MORNING in 1973, just before dawn, a ten-year-old Black boy and his stepfather began to run through South Jamaica in Queens. A white policeman had pulled up in a Buick Skylark behind them, the crunch of the car’s wheels on the pavement interrupting the quiet semidarkness. Thinking the mysterious car contained someone who wanted to rob them, Clifford Glover and his stepfather fled. The cop, Thomas Shea, pulled out his pistol and fired into the boy’s back, killing him almost instantly. “Die, you little fuck,” Shea’s partner, Walter Scott, was recorded saying on a radio transmission, though he

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

GIVEN TIME, every discussion of New York in the 1970s becomes a discussion of the South Bronx. When documentary filmmakers need to indicate the decade of New York’s municipal failure, the rubbled lots of the South Bronx mark the moment and do the failing. When overpaid Netflix directors need to gloss the Black experience in New York in the 1970s, an abandoned tenement is cast as the silent buddy. The South Bronx is a real place dogged by the surreal, somehow always most itself when on fire. But New York in the ’70s was not a burning dumpster, and the

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

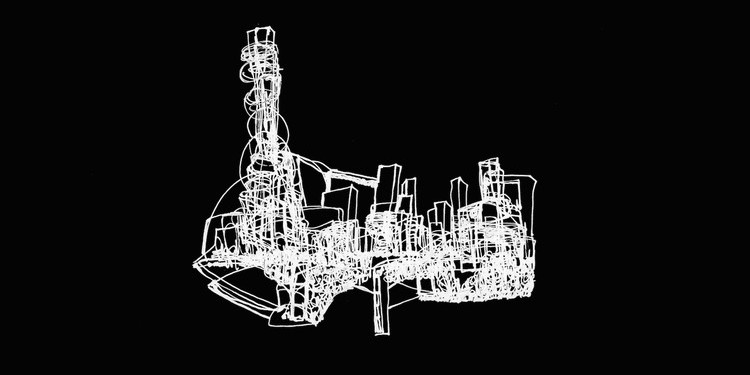

WHEN YOU CROSS the “T” in your signature with a decorative flourish you likely don’t brood on having crossed the boundary separating writing from drawing. That slender gap between visual and linguistic meaning is one explored by poet, essayist, and novelist Renee Gladman. In Prose Architectures, a volume published three years ago, she offered a series of ink drawings that resembled handwriting, architectural blueprints, anatomical illustration, maps, and scribbling while not quite resting within any one of those categories. Her drawings moved energetically between figurative and abstract elements, between the legible and the inscrutable. One Long Black Sentence extends and

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

JACQUES HENRI LARTIGUE (1894–1986), an artist whose work seems to come from another world but in reality comes from the past century, captured that era’s experience of speediness, of beauty, of carelessness, of fun. Born in fin-de-siècle France, Lartigue started shooting film as a child. Though he thought of himself as a painter first, Lartigue became famous for photographing auto races, early aviation, beachside horseplay, and society women on the Bois de Boulogne. He pioneered techniques for capturing heart-stopping proto-parkour, like a quick dandy jumping over some lazy chairs, or, in My Cousin, Bichonnade, 40 rue Cortambert, Paris, ca. 1905,

- review • July 30, 2020

In 2008, Paul B. Preciado published Testo Junkie, which is, among other things, an influential account of his illegal self-administration of testosterone gel. Stints of heady Foucauldian theory are interspersed with powerful memoiristic passages: He writes elegiacally to a friend who recently died, begins a potent affair with the French feminist writer and filmmaker Virginie Despentes, and lyrically describes the effects of testosterone on his body and mind. With a lofty sense of ritual and menace, he compares the packets of gel to “dissected scarabs, poison bullets extracted from a corpse, fetuses of an unknown species, vampire teeth capable of

- excerpt • July 7, 2020

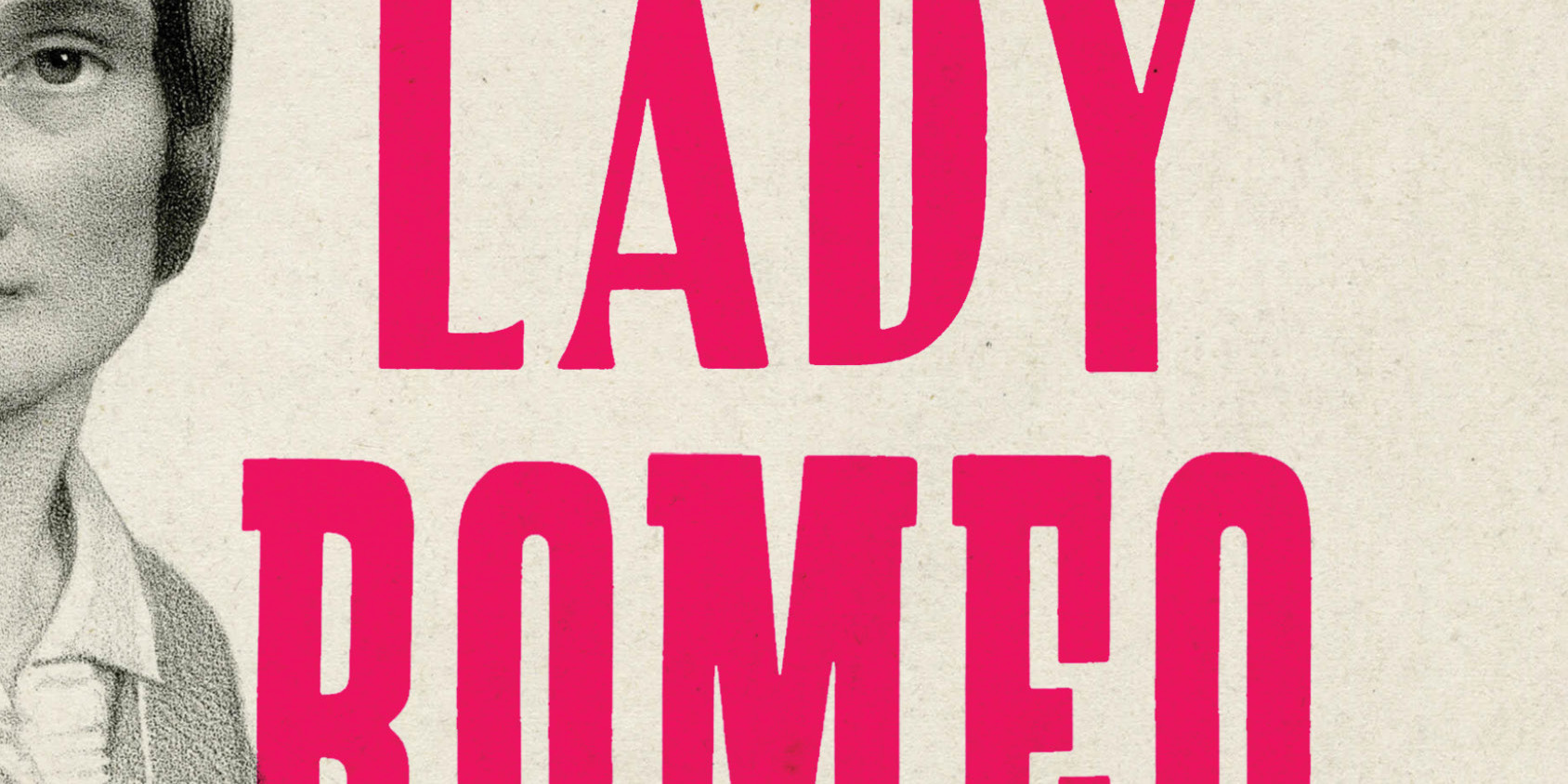

Charlotte Cushman was once called “the greatest living actress.” In the mid-nineteenth century this queer, Shakespearean performer was all the rage. Walt Whitman called her a genius, Louisa May Alcott had a stage-struck fit over her, Lincoln made her promise to perform for him (she did) and she impressed luminaries from Charles Dickens to Henry James. She rose from poverty to become America’s first celebrity, while specializing in ambitious women and transforming how we think of Shakespeare through her male roles like Hamlet and Romeo. After becoming an icon, Cushman lived openly with her female partners, facing off with critics

- review • May 28, 2020

Welcome to part three of our ongoing series about supporting the literary community during the coronavirus pandemic. This week, we focus on independent bookstores and authors in need.

- print • Summer 2020

IN 1974 DORIS LESSING PUBLISHED MEMOIRS OF A SURVIVOR, a postapocalyptic novel narrated by an unnamed woman, almost entirely from inside her ground-floor apartment in an English suburb. In a state of suspended disbelief and detachment, the woman describes the events happening outside her window as society slowly collapses, intermittently dissociating from reality and lapsing into dream states. At first, the basic utilities begin to cut out, then the food supply runs short. Suddenly, rats are everywhere. Roving groups from neighboring areas pass through the yard, ostensibly escaping even worse living conditions and heading somewhere they imagine will be better.

- print • Summer 2020

SØREN KIERKEGAARD WAS AN EARNEST, brilliant, difficult, vituperative, sensitive, sickly emo brat whose statue in the Valhalla of Sad Young Literary Men is surely the size of a Bamiyan Buddha. He was a Christian whose devoutness was so idiosyncratic as to be functionally indistinct from heresy; who lived large on family money until the money ran out and then died so promptly that you’d almost think he planned the photo finish; who tried and failed to save Christianity from itself, but succeeded (without really trying) in founding “a new philosophical style, rooted in the inward drama of being human.” That

- print • Summer 2020

DURING THE FIRST WEEKS of quarantine, I would become exasperated when I’d hear some expression of gratitude for the platforms and technologies keeping us socially connected, as though connection is only virtuous, or would be balm enough. It seemed apparent that the value of disconnection was an equally pressing lesson, a condition put before us to wrestle with, to practice, to sit with, and, perhaps, to learn from. Perhaps disconnection would even be essential to defining how and in what altered state we might arrive at the other side of this horrific, if expected, shakedown. Wanting role models for living

- print • Summer 2020

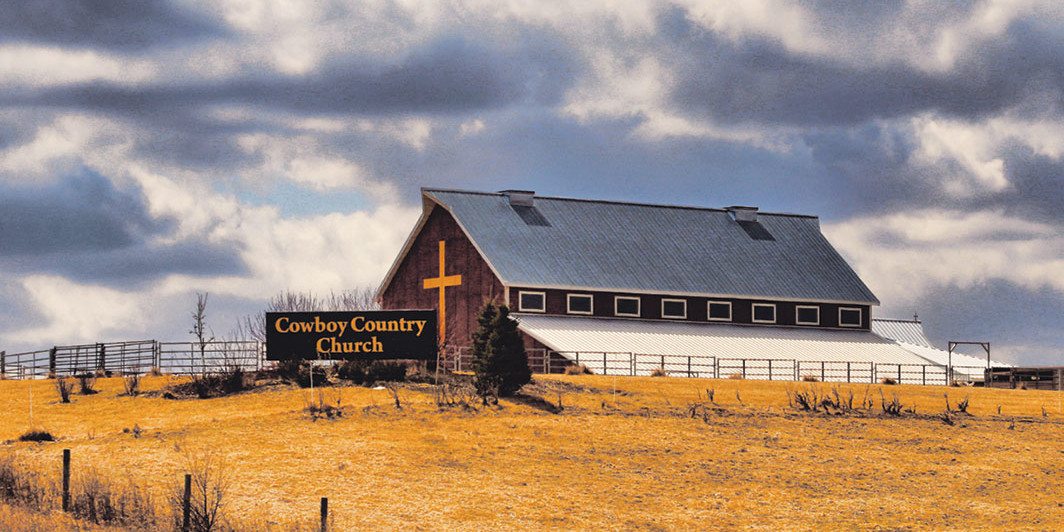

IN THE BOOK OF REVELATION, a significant influence on Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s new memoir American Harvest, the first-century prophet John is beset by visions while in exile. He sees locusts with human faces, a slaughtered lamb, a dragon with seven heads. An angel promises to condemn those who refuse God’s teachings to a fiery abyss and guarantees the return of Jesus after his people have endured a series of trials. In time, the messenger says, the old world of strife will be destroyed, and a new world will replace it. There, God will dwell with his people in peace. “And

- print • Summer 2020

IT WAS LATE ON THE FIRST NIGHT of Corona Times Passover and my teenage son chewed on a piece of matzo. Mind you, we were not following dietary restrictions. We’d had Hawaiian pizza for dinner, during which I’d rehashed the flight from Egypt, but hours later we were bored and peckish and broke in to the box of Streit’s my wife, who is not Jewish, had been kind enough to score at the supermarket.

- print • Summer 2020

APRIL 21, 2020. Last night, the crazed leader announced that he wants to ban immigration. Today I was told to prepare for furlough at my job, and I spoke to my friend who cannot get her cancer treatments. Down the road at the hospital, they are still forklifting corpses into refrigerated trucks. The price of oil has tanked. Around the corner someone has painted these words on the side of a mailbox: PROTECT BLACK PEOPLE. COVID-19. The midwife who delivered my children is begging for masks. All of the mom-and-pop shops have shuttered. The streets are littered with discarded blue

- print • Summer 2020

AS NEW YORK WAS DECLARED the COVID-19 pandemic’s epicenter, the ghost of Dorothy Parker began turning up in my bedroom at daybreak. “What fresh hell can this be?” Parker whispered, an earworm I could not stop hearing. They say the cure for an earworm is to listen to the song in its entirety; in my case, I thumbed through the morning’s headlines like a drowsy automaton until a fuller, worsened picture of our city’s new netherworld emerged.

- print • Summer 2020

TRISTRAM SHANDY sailed into eighteenth-century literary history alongside such bawdy picaresques as Tom Jones. But unlike the rest Laurence Sterne’s creation is an antinovel: It starts and stops, has entire pages that aren’t even text—blank or solid black or marbled or filled with lines and swirls that indicate the wayward shapes of the narrative (at such moments it seems like what Sterne really is is a concrete poet). On the occasions when the author doesn’t want you to know what naughty thing he’s saying (though he quit being a minister to write, Sterne was still a modest man) there are

- print • Summer 2020

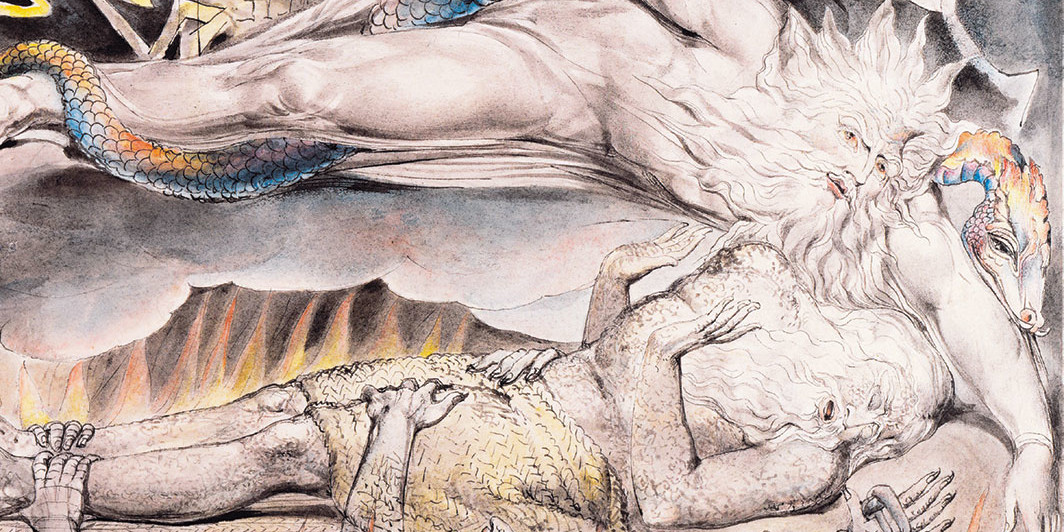

EVEN AS A LITTLE GIRL, Benedetta Carlini, born in a Tuscan mountain town in 1590, had the kind of persuasive charm possessed by politicians and good salesmen. When she played with a feral dog and it attacked her, she told her parents that the dog was the devil, come to earth to torment her. When she was caught playing with a nightingale, then thought to be a dangerous symbol of sensuality and lust, she explained that the bird was a guardian angel. After Benedetta joined a convent of Theatine nuns in 1599, she began having revelations from God. In one

- print • Summer 2020

RECENTLY, MISSING THE BALLET PERFORMANCES I’d planned to attend this spring, I revisited a short video-installation piece I love: En Puntas by Javier Pérez, featuring a ballerina with long knives strapped to the soles of her pointe shoes. It was filmed in the Teatre Municipal de Girona, in Spain, in 2013. The dancer, Amélie Ségarra, sits on the lid of a baby grand piano, tying the pink shoe-ribbons around her ankles. With the help of a rope dangling from the ceiling, she hoists herself up until she’s balanced on the sharp tips of the knives, her feet hovering eight inches