Please don’t bury me Down in that cold, cold ground No, I’d rather have ’em cut me up And pass me all around —John Prine, “Please Don’t Bury Me” Fearful indeed the suspicion—but more fearful the doom! It may be asserted, without hesitation, that no event is so terribly well adapted to inspire the supremeness of bodily and of mental distress, as is burial before death. —Edgar Allan Poe, “The Premature Burial” There could be unexpected chiming or clanging. —Lorrie Moore, “Author’s Note” to Collected Stories IF THE STRANGEST THING ABOUT LORRIE MOORE’S COLLECTED STORIES is that it didn’t exist

- print • Apr/May 2020

- print • Apr/May 2020

SET THE NIGHT ON FIRE, written by Mike Davis in collaboration with historian Jon Wiener, is a kind of sequel to City of Quartz, the cultural analysis of Los Angeles Davis published in 1990. In the beginning of CoQ, Davis described the focus of that book as “the history of culture produced about Los Angeles.” And that is true for roughly two hundred pages of CoQ, as Davis reviews the work of California historians like Carey McWilliams (he approves) and “the European reconceptualization of the United States” carried out by Los Angeles transplants like Theodor Adorno (he’s torn). Davis also

- print • Apr/May 2020

WHENEVER I SEE A COPY OF A ROBERT STONE NOVEL in a used-book store, I buy it, pretty much to introduce him to others, to press his work upon others. I recently acquired a copy of A Flag for Sunrise, one of his masterworks—1981 first edition. Out of print. Nine dollars. Between its pages, a folded note. Black ink. Neat handwriting. Life is hard. We’re trying to prepare you for that. Make mistakes . . . fine . . . good. But make them because you don’t know. Learn from them. Do not make them b/c your friends are making

- print • Apr/May 2020

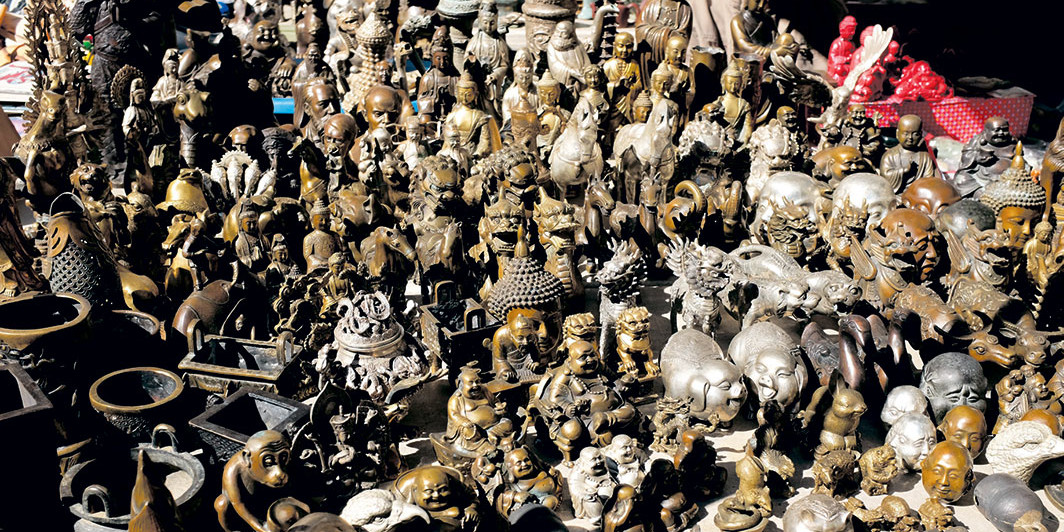

The last particule of the once-sprawling Chelsea Flea Market closed down on December 29, 2019. That remnant occupied a parking lot on 25th Street, between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, but earlier the market, which opened in 1976, had in addition comprised three lots along Sixth Avenue, as well as a garage on 25th Street, the principal setting and primary subject of this beguiling memoir. Flea markets have been in serious decline for years; in many parts of the country a “flea market” is where you go to buy batteries, aftershave, and car parts. The recent, possibly terminal phase has everything

- print • Apr/May 2020

Katie Roiphe is someone who, by her own account, writes prose as if heading into combat: She describes her preferred authorial voice as “a vehicle, a tank.” But a while back she began to feel something lacking. “My usual ways of being in the world were no longer working,” she writes at the beginning of her new memoir, The Power Notebooks. “My theories and interpretations were wrong or inadequate.” She was used to building arguments and taking stands, but she wanted to try something different—something looser, more fragmentary, more vulnerable. She began keeping a notebook where she collected thoughts on

- print • Apr/May 2020

Throughout 2015 and 2016, the US Army set off multiple clouds of deadly chlorine gas, not in some secret location in the Middle East or Afghanistan, but about an hour’s drive south of Salt Lake City. The Dugway Proving Ground, established during World War II, occupies a swath of desert larger than Rhode Island. During the war, the military built villages that resembled German and Japanese towns in order to try out weapons, including poison gas. This activity continues to the present day. In Proving Ground, David Maisel’s aerial and ground-level photos of Dugway—he reports that gaining access to the

- print • Apr/May 2020

The most popular honorary American of all time is unquestionably Jesus of Nazareth. But Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro’s latest book makes a lively case for Will as the man from Galilee’s perennial runner-up among unwitting citizens of the USA. Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Future blends Shapiro’s usual zest for unpacking time-capsule moments (e.g., The Year of Lear) with a newfound relish for Trump-era topicality. True, you may be tempted to groan at his fatuous subtitle—our future, really? Say it ain’t so, Weird Sisters. But he’s contrived an ingeniously structured game

- print • Apr/May 2020

In 1971, for the month of July, powerhouse poet Bernadette Mayer documented her life by shooting a roll of 35 mm film every day and writing down as many experiences, ideas, observations, feelings, and sights as she could. From those materials, she created Memory, a fabled work of installation art that plunged viewers headlong into the fizzing slipstream of her consciousness. Disorienting and clarifying in equal measure, Memory uncovers the space between living and recorded life. If the latter is imperative to apprehending the tumult of human experience, it nonetheless falls very short of capturing its full measure. “It’s astonishing

- print • Apr/May 2020

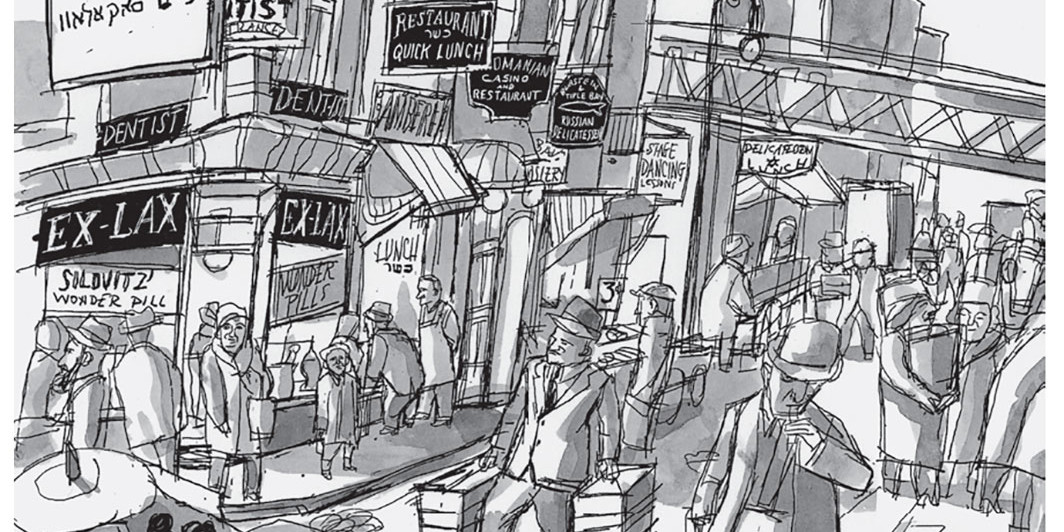

A man is what he eats. So wrote the nineteenth-century German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, and such is the premise underlying Ben Katchor’s monumental illustrated book The Dairy Restaurant.

- print • Apr/May 2020

Where most autotheory centers the life of the mind, Harry Dodge’s new memoir goes a step further, taking the mind as its matter and, to some extent, its form. The book is a brain! A peripheral brain that wonders about machine intelligence, consciousness, and itself. My Meteorite: Or, Without the Random There Can Be No New Thing sifts through a relentless stream of inputs, nestling experiences and ideas to discover what might magnetize what. Roaring with thinking, the text might like to rise up and reassemble itself into animate form.

- print • Apr/May 2020

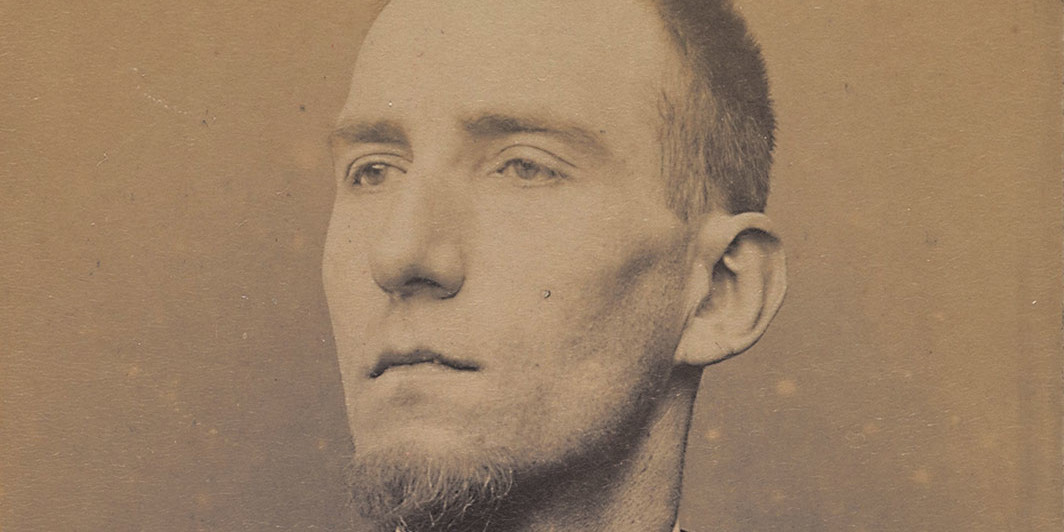

Two portraits of Félix Fénéon bookend his wide-ranging life and deeds. One, a highly stylized canvas by Paul Signac (1890) of the man as art critic, shows a “decorative Félix,” in gangly, goateed profile, proffering a lily against a background of swirling psychedelic colors. The other, a mug shot taken four years later, captures him as a prime suspect in a restaurant bombing. These twin personas, the aesthete and the activist, conspired to produce one of the truly unusual personalities of the French fin de siècle.

- print • Apr/May 2020

Abigail Heyman, Supermarché (Supermarket), 1971, gelatin silver print, dimensions variable. From Unretouched Women: Femmes à l’oeuvre, femmes à l’épreuve de l’image. © Abigail Heyman Susan Meiselas joined the famed photo agency Magnum in 1976; the women already on board were Eve Arnold, Mary Ellen Mark, Inge Morath, Abigail Heyman, and Jill Freedman. Three black-and-white photobooks […]

- review • March 24, 2020

You can tell a lot about someone by peering at their bookshelf. “I don’t like to read,” the Taiwanese writer Sanmao grumbles when she receives booklets of traffic rules before a driving test. “What are you talking about?” her husband, José, says, gesturing at her bookcase. “Here you have books on astronomy, geography, demons and ghouls, spy romances, animals, philosophy, gardening, languages, cooking, manga, cinema, tailoring, even secret recipes in traditional Chinese medicine, magic tricks, hypnotism, dyeing clothes.” This scene, from Stories of the Sahara, a collection of short travelogues set mainly in the African desert, is Sanmao distilled: a

- review • March 24, 2020

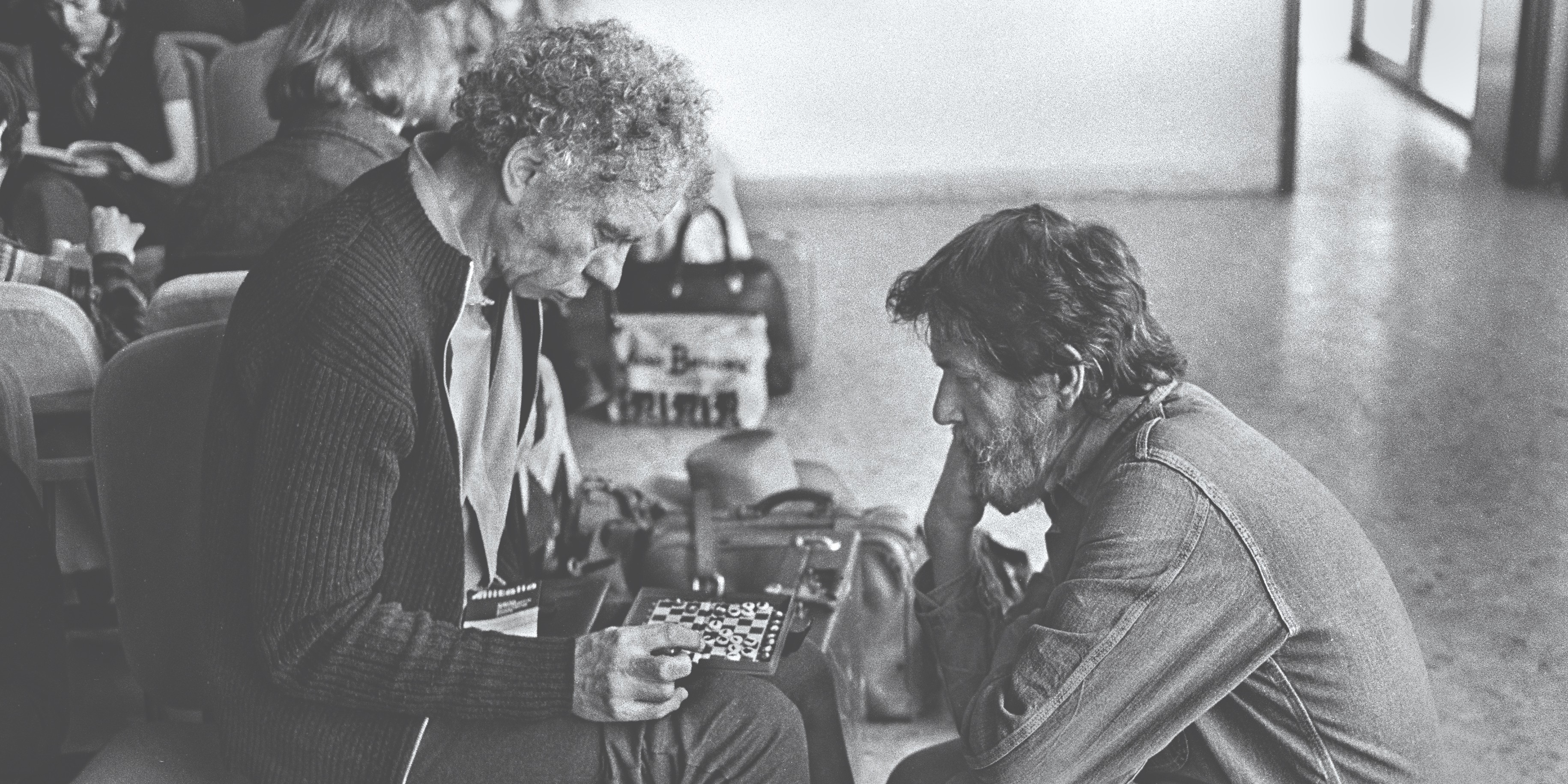

In a letter toward the end of Love, Icebox, a collection of correspondence from John Cage to his partner Merce Cunningham, doubt about their relationship creeps in. Cage, who was seven years older than Cunningham, is concerned that Cunningham doesn’t love him and “will love other misters.”

- review • March 17, 2020

Rob Doyle is a twentieth-century boy. His characters are monologous young men who get high and chase literary grouches with an eye out for that high-modernist whale, the epiphany. Many of Doyle’s contemporaries—literary men in their late thirties—confine themselves to the cramped emotional tone afforded to those invested in the internet’s panoramic view and its plausibly crushing Bad News. But Doyle looks back: His drugs and bands and writers are pre-9/11 specimens, across all of his books. The characters in his 2014 debut novel, Here Are the Young Men, are teen grads in Dublin off their faces, smack-dab in the

- excerpt • March 12, 2020

Part of a political revolution toward socialism will necessitate a revolution of values. Those values won’t come from the top down but from culture up. We can use Denning’s notion of a “cultural front”—in this case, to save us from our cultural ass. Right now the United States is working at a deficit. Our identities and aesthetics are deeply tied into capitalism—no disrespect to rapper Cardi B and her love of money, but unlearning money worship and our worth being determined by what we can accumulate is going to be vital to any socialist change. And as during the 1930s

- excerpt • February 20, 2020

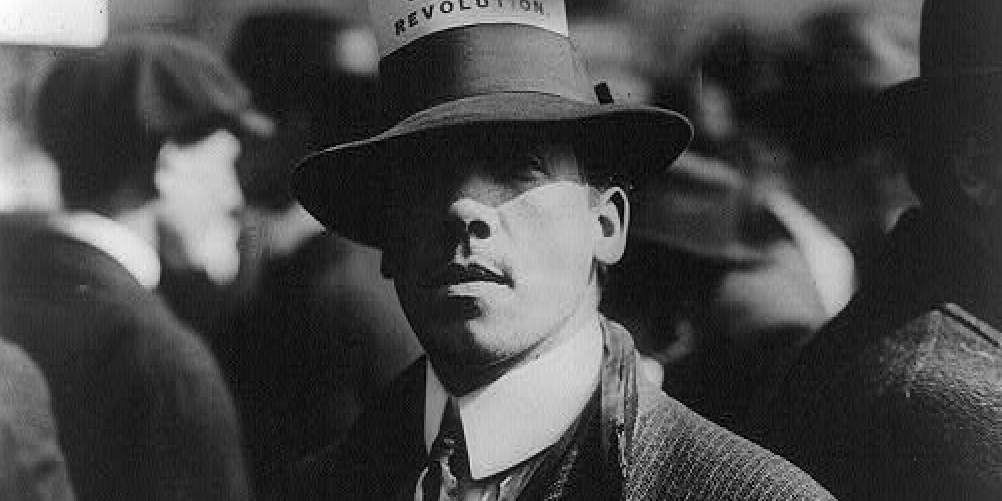

My 1915 edition of The Cry for Justice by Upton Sinclair is an evocation of a lost America. The anthology is filled with writings, poems and speeches by radicals and socialists who were a potent political force on the eve of World War. They spoke in overtly moral and often religious language condemning capitalist exploitation as a sin, denouncing imperialism as evil and vowing to end the greed, cruelty and hedonism of the rich. The fight for justice for the poor and the worker was a sacred duty. The life of the artist was a life of action. Intellectuals, grounded

- excerpt • February 11, 2020

A weeping woman is a monster. So too is a fat woman, a horny woman, a woman shrieking with laughter. Women who are one or more of these things have heard, or perhaps simply intuited, that we are repugnantly excessive, that we have taken illicit liberties to feel or fuck or eat with abandon. After bellowing like a barn animal in orgasm, hoovering a plate of mashed potatoes, or spraying out spit in the heat of expostulation, we’ve flinched in self-scorn—ugh, that was so gross. I am so gross. On rare occasions, we might revel in our excess—belting out anthems

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Nam June Paik, Bye Bye Kipling, 1986, video, color, sound, 30 minutes 32 seconds. © Estate of Nam June Paik, Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York It’s misleading that Nam June Paik has been named the grandfather of video art. Sure, he started the whole thing, but as an artist, Paik is no patriarch. […]