It’s always been a sport to argue about the canon. I’ve never been one for sports.

When readers declare a desire to read away from the canon, I admire the instinct. It’s almost a predictable part of the cultural cycle: the resurrection or rediscovery of those whom the times have left behind or unjustly ignored. It’s thrilling to reckon with the work of artists never given their due—in recent years, Jean Stafford, Elizabeth Hardwick, Lucia Berlin, Kathleen Collins, Alice Adams, Bette Howland. But I confess: it rankles, a little, the cri de coeur “Read Women.” There’s a long list of reasons to read Bette Howland’s work; I’m not sure I’d put the fact of her womanhood anywhere on it.

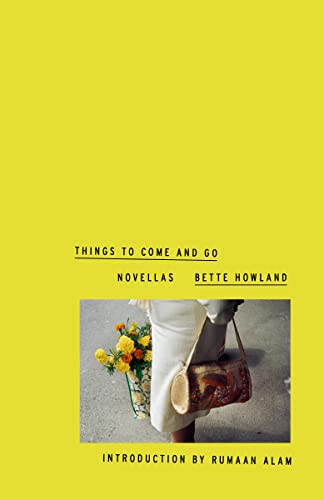

Bette Howland was born in 1937. In Chicago, as is clear if you even glance at her work. She studied at the university of that town. She married. She had two sons. She divorced. She wrote short stories. She published these—and other pieces—in small magazines. She befriended Saul Bellow. She went off to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She moved home, scratched out a living as a librarian and editor. Her first book, 1974’s W-3, is a memoir recounting her time in a psychiatric hospital (Howland took a bottle of sleeping pills, while in Bellow’s apartment . . . yikes). Things to Come and Go, published in 1983, was her last book.

This kind of biographical sketch doesn’t get anywhere close to the real life. Weirdly, even her own memoir can’t. Howland is in that book, sure, but the author is more interested in the other patients she meets, in the hospital’s rooms, and staff, and rites, in the city outside its doors. Maybe that’s telling. A fool’s errand to seek the fact in fiction, but Howland’s stories, collected in Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, perhaps better explain who she was than her memoir, or than I could here.

In her stories, so often, there’s a first-person narrator who wants to tell us about everyone but themselves. That’s true of two of the pieces in this volume, as well: “Birds of a Feather” and “The Life You Gave Me” each contain an I who is stubbornly elusive. Howland will forgive me if I thought of this narrator as the author herself. She’s good company, cracking wise about everything and everyone she sees. She darts off the page when you try to get a look at her. It’s a strange, disobedient way to use the first-person perspective, a stroke of genius, maybe. But even if we read this I as the author (I’m aware this is against the rules) it isn’t self-effacement. The writing of fiction is an act of ego. Of course that I doesn’t want to reveal herself! She wants to show us the whole damn world.

It’s so tempting to turn the Overlooked Writer into a parable. But maybe that renders her flat in a way she’d never allow in fiction. Bette Howland juggled shitty jobs and two kids and mental illness. That’s difficult, unenviable, unfair, but it’s life. That she still sat down to write seems the opposite of tragedy. She was an artist. She did it. There was an urgency for her, to create, and she met it. Seems incredible to me. Don’t read Howland’s work now because it was impossible for a woman writing in the latter part of the twentieth century to get a fair shake (still true, sorry); read it because it demands to be read.

In high school, I was taught that a novella is a long story that can be read in a single sitting. We must have been talking about The Old Man and the Sea. It was asserted that this definition came from Henry James himself, as though that meant anything to a bunch of fifteen-year-olds. With the benefit of age, I understand that surely Henry James and a mother of two young kids in a cold apartment in Chicago would not agree on what a sitting is.

Forgive me, but I don’t think the novella really exists. It’s not like sestina or ballade or haiku (bless the poets for their specificity), something with clear rules and parameters. Novella is wishful thinking more than literary form, a way of willing a short story closer to a novel. It implies that we want more. And I confess I do. Take “The Old Wheeze,” the central piece in this collection. I would read three hundred further pages of it: the stoic babysitter, the young divorcee, her brawny suitor (“He had not forgotten what everyone must know, once up on a time; how ridiculous, or frightening, or both, most grownups must seem to a child”), even Mark, the rare fictional kid who feels like the invention of an artist who has, at some point, known a child.

Maybe wishing there were more is lamentably predictable, bigger-is-better thinking on my part. In forty-two pages, Howland gives us the proud and prim sitter, the pretty mom, the man eager to sleep with her, and even Mark, “What he wanted—all he wanted—was to smell his mother’s cheek.” Perfect. I love Henry James, but he spent forty-two pages on whether a Eurotrash prince would buy a golden bowl (spoiler: he doesn’t). Henry James was rich in sittings. Bette Howland was not.

No matter. She had an ear. What more do you need? It has to have been what Bellow liked about her (that and the fact that she was half his age). It’s the sentences, which sound like music, which hold a smile more than a laugh. This is from “Birds of a Feather”: “How’s my little bright-eyes, huh? My besty little Esti? (That was my name.) Tee Gee. Another Beautiful day. (Honey never spoke the name of the Lord; she used initials.)”

Howland’s writing is the only argument for reading her that you need. “I must have been a sourpuss,” the narrator of “Birds of a Feather” explains. “That’s what I think. People were forever teasing me, making faces, popping eyes and poking out chins. It was a long time before I caught on; they were imitating me staring at them.” Howland stared at the world. What she saw is still right here, on the page. Things do come and go. But art, sometimes, lasts.

Excerpted from Things to Come and Go by Bette Howland. Introduction copyright © 2022 by Rumaan Alam. Reprinted by permission of A Public Space Books.