Perhaps it is the contemporary tension around the concept of selling out that has made so many recent works of fiction deal with the question of their own economic conditions of possibility, their marketing, and their commodification explicitly within their pages. One of the clearest examples of this is Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure. The protagonist of Erasure is an experimental novelist, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, who is dismayed by the outsize success of a novel entitled We’s Lives in da Ghetto. Monk sees this book as cynical attempt to give the white public a story of Black experience that conforms

- excerpt • August 4, 2021

- review • July 20, 2021

In one of the stories from Prepare Her, Genevieve Plunkett’s debut collection, a pair of newlyweds who grew up together are staying at a mildewed, hot cabin on their wedding night. It is a makeshift honeymoon at a camp the groom’s grandfather owns. For the special occasion, they begin to drink wine. “We couldn’t think with all the heat and noise and so we began to talk instead,” the narrator recalls. “We said things that could not be taken back. All of this chatter, in this womb-like environment seemed safe at first—daring and intimate.” The atmosphere almost imperceptibly becomes stifling.

- review • June 10, 2021

Broken People opens, like many stories of discontent and yearning in Los Angeles, at a dinner party. This isn’t the perpetual glamour of an Eve Babitz novel, or even the disaffected rich kids of a Bret Easton Ellis one. Sam Lansky offers a more familiar alternative. His protagonist is an aimless, semi-successful, recovered drug addict committed to self-sabotaging the last of his twenties. Sam feels a deep unbelonging at the party; as we come to learn, Sam feels unbelonging in most places. Finding himself in a conversation about ayahuasca, he dismisses it as “a thing trendy, wellness-minded people were doing

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

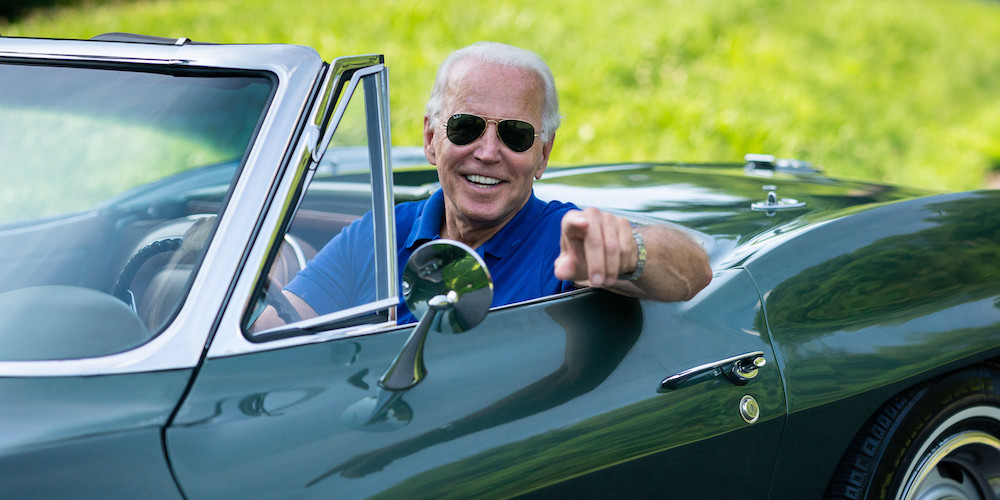

WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE NARRATIVE MODE to capture the last few years of US history? What mode will fit the times going forward? Political eras lend salience to certain sorts of stories. We have just lived through a gothic phase of history, and a new sentimental age is upon us. These two modes of narrative have been alive, if not always dominant, in America since the eighteenth century, and they have lately defined our politics. The tropes of the Trump administration were those of a gothic nightmare—sexual perversion and predation, the sinister influence of forces emanating from the shadowy east,

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

HUMOR CAN BE A RISKY BUSINESS. For the comic, professional or not, comedy evinces parts of the self that may not otherwise see outward expression. For the reader, the line between mirth and madness can be thin. In The Republic, Plato, perhaps history’s foremost derider of laughter, reasons that elites must refrain from laughing because it signals a loss of control, a condition that can be exploited by the masses. Comedy must be left to the marginalized—“slaves and hired aliens,” as he puts it in The Laws—because someone needs to participate in the ridiculous in order for the serious to

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

THE MOST STRIKING FEATURE OF THE NEW WORK BY ANDREW O’HAGAN is the hole in the middle of it. Mayflies’ first half is set in 1986, its second in 2017 and 2018, and in between there is a blank you would need a bigger novel than Mayflies to fill in. The narrator, Jimmy Collins, goes to sleep at age eighteen, having spent the night dancing his author into run-on sentences at a warehouse party in Manchester. In the next chapter, he’s near fifty. It’s one version of a hangover. Now a writer rather like Andrew O’Hagan, Jimmy sees the traces

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

I SUPPOSE THE FANTASY SUBGENRE OF “ALTERNATE REALITY” doesn’t altogether count as fakery since such storytelling is usually up-front about its artifice. Nevertheless, I am an easy mark for “what-if-the-Nazis-or-the-Confederacy-had-won” stories and their ilk wherever I can find them. My latest guilty pleasure is For All Mankind, an Apple TV streaming series that imagines what the latter half of the twentieth century would have looked like if the Russians had beaten us to the moon.

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

IN “WHAT IT IS I THINK I’M DOING ANYHOW,” written in 1979, Toni Cade Bambara lays bare the bones of her writing life. Short fiction had her heart, she said, having released by then two separate collections, Gorilla, My Love (1972) and The Seabirds Are Still Alive (1977). “The short story makes a modest appeal for attention, slips up on your blind side and wrassles you to the mat before you know what’s grabbed you.” This she found suitable to both her temperament and schedule, completing her work between time as a mother, partner, worker, and community member. “I could

- excerpt • April 26, 2021

He climbed to the top of the tree. The freight still passed, its many-colored, many-shaped cars looking like the curious shapes of a puzzle.

- excerpt • April 19, 2021

This morning a boy passed by my house.

- review • March 30, 2021

“PRET,” “SECOND PRET,” and then, a little later, “another PRET.” The protagonist of Rebecca Watson’s Little Scratch makes these half-conscious mental notes of the homogenous sandwich shop as she hustles through London to get to work on time on a Friday morning. Moments later, she looks up, absorbing the beauty of the “widescreen sky,” before almost immediately being “struck by / how irritating it is / that it is here, / here, with all these men in suits, all these watch shops, that I am / seeing beauty.” The oppressive banality of London’s glassy, late-capitalist grind is ever-present in the

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

RARE IS THE ART CRITIC who writes novels, though I’ve never really understood why. In 2012, I asked eminent art essayist Lucy R. Lippard about her only published work of creative writing, I See / You Mean (1979). She sighed and said, “I thought I was going to be a great novelist. . . . I was not a great novelist.” Not so rare are fiction writers and poets who pen art criticism. Lippard’s contemporary Susan Sontag famously thought of herself as a great novelist first. In the 1980s, Lynne Tillman began to mix genres in her “Madame Realism” fiction-essays.

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

IN THE ANTIC TALE that opens The Cheerful Scapegoat, Wayne Koestenbaum’s book of self-described “fables,” a woman named Crocus, like the flower, arrives at a house party wearing a checkered frock designed by the Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She cowers in the entrance, vacillating over whether to enter or not. She phones her doctor, a man whom she refers to as the “miscreant-confessor,” who entreats her to be social. Inside, Crocus accompanies a “fashionable mortician” to a bedroom where she happens upon a fully clothed woman lying atop a fully clothed man. Observing something “unformed and infantile” about the man’s

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

A DECADE AND A HALF AGO, a book so enchanted me that it was hard to pull away. If I were to get any of my own work done, I needed to hide it. (The book was very long, over eight hundred pages; I didn’t have the time.) But the tome kept jumping back into my hands. I could have given it away, of course, or simply tossed the thing, but surely at some point—when this oppressive spell of work was over—I’d want to dive back in. I had only finished a third, perhaps less. One day, I came across

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

THE LIFE OF THE MIND, Christine Smallwood’s debut novel, begins with an ending. We meet Dorothy, a contingent faculty member in the English department where she used to be a doctoral student, as she negotiates the miscarriage of an accidental pregnancy. The pregnancy, at once unexpected and welcome, is a blighted ovum, “just tissue” according to her ob-gyn. The metaphor is clear: Dorothy’s academic career and the pregnancy are both projects of development and growth that never had a chance to thrive.

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

KLARA, THE TITLE CHARACTER OF KAZUO ISHIGURO’S new novel, would seem to have some serious shortcomings as a narrator. Introduced in a retail outlet in an unnamed city where she alternates between the window and less desirable display positions, Klara is a solar-powered AF, or Artificial Friend, who exists solely to assist and accompany the human child who purchases her. Despite her impressive capacity for mimesis and spongelike powers of absorption, we never forget Klara’s obvious limitations. Her view of the world is circumscribed, her vocabulary stilted, her agency virtually nonexistent. All of which make her an oddly perfect fit

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

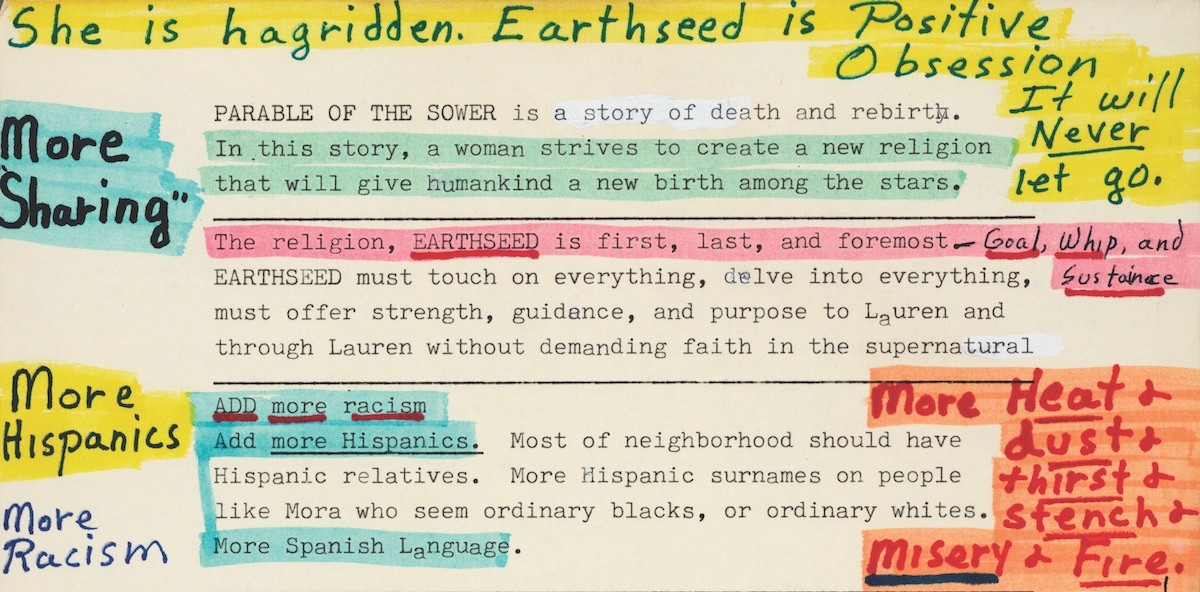

ONE DAY IN 1960, when she was thirteen, Octavia E. Butler told her aunt that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up. She was sitting at her aunt’s kitchen table, watching her cook. “Do you?” her aunt responded. “Well, that’s nice, but you’ll have to get a job, too.” Butler insisted she would write full time. “Honey,” her aunt sighed, “Negroes can’t be writers.”

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

TORREY PETERS HAS BEEN self-publishing and giving away her stories online for pay-what-you-like prices since the mid-2010s. In the short works The Masker, Glamour Boutique, and Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones—a sci-fi contagion story about hormones—Peters zeroes in on moments when her trans protagonist behaves or thinks in ways that communal consensus has agreed is “wrong.” Peters simplifies nothing, explains nothing to the outsider, which is why she is treasured by readers who are also protective of her and her work. For as long as such stories have stayed in the underground, where people make an effort to understand

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

THE FIRST HALF of Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One Is Talking About This opens in a place between life and death. The second half unfolds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The first half is about the internet. The second half is about having a body in a world. These halves are as discrete as a clunky little screen glowing its gloamish light into an open face, two limitless modes that find their limit only where they merge. The novel takes shape in the parenthetical scoop of a Venn diagram between machine and mind, crowd and solitude, joke and beauty.