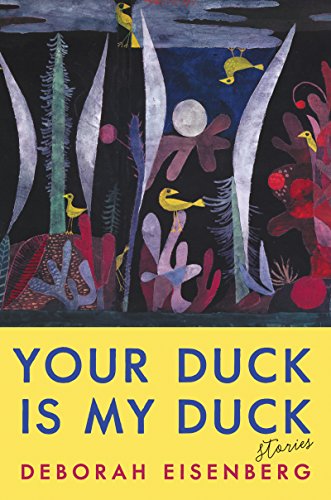

Over the span of thirty-two years, Deborah Eisenberg has produced five short-fiction collections, each more emotionally thoughtful and rigorous than the last. Like her past work, Eisenberg’s newest collection, Your Duck Is My Duck, requires not just a reader’s utmost attention, but also a willingness to be vulnerable and receptive. Rather than concern themselves with plot in an obvious way, the stories tend to chase abstract questions and explore how time impacts those pursuits. In “Taj Mahal,” a group of actors reflect on a tell-all about their colleague, with each character remembering both the subject and shared events differently. In “Merge,” Eisenberg confronts privilege through the story of a well-off young man indifferent to the increasingly indecipherable postcards sent to him by his long-distance girlfriend. Eisenberg’s stories rarely offer any form of resolution beyond the hope that somewhere, maybe, resolution exists.

On a hot Friday afternoon in August, Eisenberg was kind enough share a pot of green tea with me, and discuss her new collection, the struggles of writing, and how her work has shifted over the span of her career.

I wanted to start by asking how you felt about the new collection.

I’m very pleased that a significant proportion of my life—twelve years—is represented in a physical object now. I don’t know how readers will feel about it.

You think the work is that difficult?

I don’t think it’s difficult, but you cannot read those stories when you’re asleep. So much of reading is about dropping what is already in your head, and making that space available to someone else’s mind. I think readers have to engage quite actively with my fiction. Frankly, I find ingratiating fiction very distasteful.

Of course there are spectacular writers who are not at all ingratiating, but still let the reader lie back and be thrilled by the ride. Alice Munro, for example. Her insight and confidence are exceptional, so part of the cleanliness of it is the drive and direction. She has that particular gift of seeing things in a shapely way, seeing life, in her case truthfully and with spectacular insight, as story. In a certain way, “story”—that is, a narrative arc with a beginning and an end—which so often feels artificial to me, is almost the reverse of the way I see things.

There is a lot of focus on the movement of time in your work, or at least a sense of a person in some kind of transit. In the new collection, the one thing that really stood out to me was the focus on death and what we owe each other. What shifts invited this deeper focus into the collection?

Age, no doubt. My own age, and the apparent looming death, by murder, of the planet. They appear to be coinciding, I’m sorry to say. For a few years, I and a number of people I knew who were roughly my age and older were always sitting around scratching our heads, saying, “Do I just think we’re at a possibly terminal moment of human history, or is it because I’m at my own possibly terminal moment?” Now it is pretty clear that between nuclear war and climate change, we’re in mortal danger.

I was fortunate to be young in a period that was very expansive. You know, it was always terrible in this country if you were poor, especially poor and of color. I mean, many things were always terrible. Many people remember the 1960s, for example, as a rosy, marvelous time—it wasn’t. It was extremely violent. It was filled with conflict; but it was also filled with hope and exciting prospects of change. We are currently in a period that is depleted of hope to a great extent, though not entirely. How could that not be the case when what we see around us is conscious and enthusiastic cruelty, and real sadism. So, I’m in an odd position of contemplating mortality from two different vantages, one personal and one not personal. It is fascinating. Being old I find really fascinating. I would say that the book is saturated with considerations of mortality and disappearance.

The stories in Your Duck Is My Duck deal with the limits of memory, and how it shapes our values and conflicts as we age. What interests you about this intersection of time and memory?

I’m interested in what most of us are interested in, which is, What is it like to be a human being on this planet? What are we? So, of course, the human experience of time is so fascinating because humans are so acutely aware of time passing. Obviously other animals have a sense of the future, and some kind of sense of the past, but I wonder if other animals don’t have a much more concentrated sense of the present, at the expense of a sense of the past or future.

It’s very interesting to me that we’re going along two simultaneous tracks at once, one being the experience of the body in time as it gets older minute by minute, and the other being the experience of the mind, which accrues experience, but doesn’t really relinquish any. I have a terrible memory myself, but everything one experiences has some sort of impact on your brain. For example, I’m seventy-two. One is seventy-two, but not exclusively seventy-two, because one is also all the other ages one has been. Certain experiences I had at seven are as alive to me as experiences I had yesterday. That is one of the fascinating things about age—you’re moving through this medium that’s very dense with sensation.

How do you feel when readers accuse you of not being “realistic” or “relatable” enough in your writing?

I don’t require people to like my writing. If they do, great. If not, too bad. It used to hurt my feelings if people didn’t like it, but now I don’t really much care. I’m much more concerned with whether or not I respect the people who like my work, and I have to say that I have no complaints. I have the audience I want, and I don’t care if it’s a big audience or not. I’ve never particularly aspired to a large readership. I feel very happy and satisfied with the readership I have.

You’ve said before that up until thirty, you had no idea what it was going to be. So now that you’ve kind of been on this path and keep writing, are you ever still surprised?

This is impossible. I can’t do it. Way back in our conversation, you and I were talking about that sense of knowing when something works or not. If something doesn’t proclaim its total worthlessness, if it doesn’t just lie there on the floor gasping its last, you have to keep going with it. You have to keep working on it. Even if you say, okay, I give up, I quit, it’s defeated me, it’ll show up on every piece of paper you pick up until you’re done with it.

Eric Farwell is an adjunct professor of English at Monmouth University and Brookdale Community College in New Jersey. His writing has appeared in print or online for Esquire, Salon, the Kenyon Review, the New Yorker, McSweeney’s, the Village Voice, and Vanity Fair, among others.