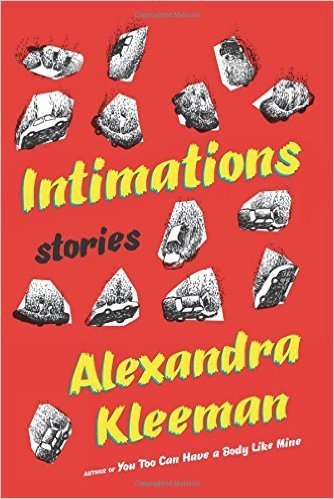

Alexandra Kleeman’s fiction may share affinities with the luminaries of our postmodern canon—Don DeLillo, Robert Coover, and Ben Marcus—but her sensibility equally recalls the films of David Lynch. With an eye toward the macabre within the mundane, Kleeman’s fiction tantalizes and spooks, thrusting the reader into bizarre worlds of dream logic. Each of the twelve stories in her new collection Intimations are enigmatic fables bound by a sense of emotional urgency: In the opening story “Fairy Tale,” a woman finds herself at a dinner table with her parents, where they are joined by a group of unfamiliar men who each purport to be her partner or paramour; in “You, Disappearing,” things vanish without warning in a fading post-apocalyptic landscape; in the story “Intimation,” the narrator is trapped in a doorless apartment with a strange man who acts like he is her boyfriend. Menace lurks around every corner; in one story, even lobsters seem threatening. Throughout, her female protagonists grope through dark rooms in search of safety and reason, desperate to configure themselves to the blurry entities around them. To encounter the everyday as if for the first time—as a child would, perhaps, or as one still dreaming—is to see the banal for what it really is, as a baffling series of events without enduring logic.

I met with Kleeman earlier this month at a café near Columbia University. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Why do you think your stories so often feature characters in these dreamlike situations where they must figure out the rules of the game as they go?

I think there’s a deep connection between literature and dreams. When you open up a book, you’re opening yourself to the fictive environment of that book. As a writer, you can place yourself in a similarly open, observant state, waiting to receive the rules that make up the world that you’re trying to create. For me, this raises the stakes and makes the process of writing more surprising. If I conceive a character with a thorough, fleshed-out biography, they always act in a way that feels predictable to me. I’ve calculated what they’re going to do based on things I’ve already decided about them and it feels so authoritarian. Instead, my characters often wake up in situations and then are told who they are.

And so often your protagonists are women trying to follow the script of femininity—they’re expected to be mothers, daughters, lovers—against their will.

Yeah. There’s a script for masculinity too, but the script for femininity is longer and more detailed and is much more structured—a structure that is imposed and felt. When I studied cognitive science in college, I was always fascinated by theories of embodied cognition: We talked about how even looking at a tool or hearing the name of a tool activates the muscles that operate that tool. So a hammer is, on the one hand, just an arbitrary shape, but because we know what it’s for, our bodies react to it with the learned response. But the tool’s purpose isn’t innate: it’s cultural, it’s social. And being a woman, I’m often aware that some kind of behavior is being asked of me and I’m making a conscious decision about whether I want to perform that behavior or not.

I’m making a chilling connection between women and instrumentality.

My characters often feel an affinity for objects too. They’re fascinated by an object’s function, which is both ingrained and arbitrary. For instance, in the story about the lobsters, the characters come to an awareness that lobsters are meant for eating. They exist to be caught, boiled, chopped. The protagonist understands that she’s meant to tear them up and consume them. She hasn’t been shown any other options. But can she invent a new option?

I think my characters are often asking themselves: “Can I choose nothing?” But there’s no way to choose nothing, because not choosing still drives the situation forward. You’re always doing something that affects the situation. Many of the doors are locked or absent, but even if they were there, they’d still open on to a situation that had similar limitations.

Is that why do you tend to gravitate toward stories of menace and dread?

I like menace, dread, and fear because they’re all feelings that involve a heightened sensitivity to your surroundings. The only time you aren’t feeling strange or oversensitive or menaced is when you’re closing off part of the world to yourself, artificially streamlining or simplifying. When you’re afraid, you suddenly become aware of how many things can possibly happen to you, and how little you actually know.

When I was plotting some of these stories, I was interested in starting from fear and seeing where else you could end up emotionally without resolving the thing that caused the fear. That’s really interesting to me. I can imagine a full story arc, but I’m more interested in beginning with an unsolvable problem and figuring out some way to continue on from there.

I often think of Plato’s idea of anamnesis, the idea that we possess knowledge from our past incarnations, forget that knowledge when we’re born, and then go through life learning what we’ve forgotten. I don’t like Plato much in general, but I like this idea—with some modifications. I feel that we’re most helpless at the beginning and end of our lives, when we know so little about our situation and are aware of how vulnerable we are. In the middle of our lives we forget this, and so we struggle all the time, against trivial things or crucial things, and more or less lose that one coping strategy of the very young and very old: to adjust yourself instead, and accept things the way they are.

How has your biracial background shaped your writing? Do you ever feel pressured to write in a certain way?

Biraciality shaped my writing in a sort of subterranean way. I moved a lot when I was growing up, and we moved into and out of areas that were Asian-friendly to varying degrees—for a year I lived in a largely-Asian San Gabriel Valley suburb, at other times I went to schools where nobody had even heard of being Taiwanese, and where the nearest Asian grocery store was an hour and a half away by car. Being biracial means that you’re a Rorschach test for the people you encounter. Everyone wants to tell you what you look like. I’ve had people tell me I’m wrong about my ethnic makeup—that “someone on one side or the other” must have had Russian blood, or that I “really look more Japanese.” I always felt like what they saw didn’t have much to do with me—I had a face that could be read multiple ways, and because I was female my body was considered an object for public viewing. This dissociative feeling was just something that came along with moving through the world. Sometimes I feel they just wanted to include me in something, by force. I use that feeling a lot, of a character resigned to being deformed by the way other people see them.

Because I felt so displaced so often, I never became completely comfortable with a biracial or white or Asian identity. My dad studied ancient China and my mom studied Japan, and I spent more time in Japan than I ever did in Taiwan. I knew each of those cultures was distinct, and I didn’t know how they went together. I identified with the specifics, this Japanese novel, that Vietnamese friend. But when I write I’m interested in flattening, in making things generic or cryptic or opaque. I feel I can play with those effects within the tropes of a mainstream, “unmarked” white culture because that culture has already tried to make itself standard. I’m not necessarily erasing anyone or anything; I’m working with vacant tokens.

What kind of writing influenced you early on?

Going super far back, a lot of Japanese literature that I took from my mom’s office. Science fiction, a Philip K. Dick story collection that my dad had bought and forgotten about. At that age, I didn’t even know if I liked it or didn’t like it, I just knew that after I read “The Father-thing” I slept badly for a whole week.

Samuel Beckett was really important to me, and he was the first person I read that made me think maybe I could write fiction. In his fiction, plots seemed to work cumulatively instead of through a clear storyline or plot arc. The situation was the story, and the situation was inescapable.

I read a lot of fairy tales too when I was young. I had a few collections of fairy tales that were written in this very fleshed out Victorian style. They were for adults possibly. A lot of them were really similar to one another, but they would present themselves as wholly new stories—so I would hear the echoes of all these other stories as I read. There was something strange but comforting about reading something new that unfolded just as you expected.

Anelise Chen is the author of the novel So Many Olympic Exertions, forthcoming from Kaya Press in Spring 2017. She currently teaches writing at Columbia University.