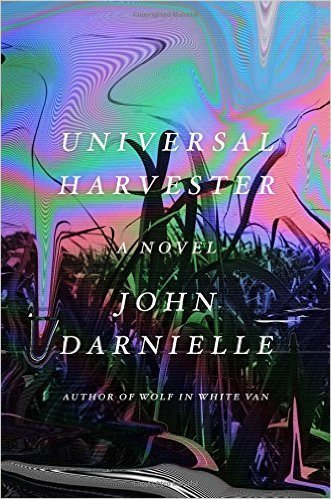

John Darnielle is a master of sympathetically depicting his characters, both in his music (he’s the front man of the indie-folk band the Mountain Goats) and his novels. In both mediums, Darnielle renders his subjects—whether they are weirdos, sinners or some combination of the two—with tender empathy. His new novel, Universal Harvester, details the lives of Jeremy, a video-store clerk, and Stephanie, the schoolteacher he has a crush on. When they stumble on a number of mysteriously edited tapes that contain disturbing footage, they’re pushed to explore the hidden, sinister side of their small Iowa town. Rendered in hyper-realistic prose, the novel unfolds slowly, and Darnielle makes the mundanity of small-town life seem as terrifying as the disturbing films.

I recently spoke with Darnielle by phone on a wintry morning. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Universal Harvester is about two individuals who can’t leave a mystery alone. What drives this pursuit? Are they trying to find a compromise between tolerating the mundanity of small-town life and fleeing from it? Or is it something deeper?

I think it’s both. The tension between Jeremy and Stephanie is that Stephanie desires to see what’s going on, and Jeremy desires to maybe let things remain as they are, at least initially. I grew up in California, where turning over a new leaf was a natural inclination. One thing the book deals with is what happens when you turn something over. There are these external tapes, but they stir up something internal. Jeremy and his father also have a lot of grief over the death of Jeremy’s mother, and this grief both invites curiosity and shuns it. If you leave it alone, it might fester. If you don’t leave it alone, there’s a worry it might crush you.

There’s a clear sense of sympathy for all of these characters in this book. The same thing can be said of how you portray the protagonist in your first novel, Wolf in White Van, and many of the characters that populate your songs. Why are you drawn to slightly downtrodden or otherwise average individuals?

As a kid, I would read books like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe where evil wouldn’t be punished. I didn’t want anyone to suffer. I’m Catholic by rote, so part of the fascination with suffering comes from that. But when people are suffering, I want them to feel better. As a grownup, I recognize that it doesn’t work that way; you can’t just remove someone’s pain like that. But that instinctive reaction—to comfort—remains. Also, as a kid learning about American literature, I really clicked with Walt Whitman’s impulse to write about people that readers will recognize. Even though there’s a lot of beautiful writing that came out of the nineteenth century, I struggled with literature from that era a bit: It was hard to understand people’s lives because I felt like their values were so alien to me. Even now, I want to always write in a way that will be relatable for myself and my readers.

The novel does a terrific job of capturing the eerie menace that farm towns seem to contain, especially to an outsider. Do you think the disturbing qualities of the videos would resonate in the same way if you had chosen, say, a dark basement or a run-down apartment instead of a spacious barn? How valuable is the farm itself to the fabric of the novel?

I think your reaction is a fairly typical one for someone not from the Midwest. For those who didn’t grow up around them, farmhouses and silos are creepy. The truth is that these places are fading away as the industry changes. They’re kind of like gothic mansions in many ways, because they’re disappearing as big farming becomes more dominant.

When I was working on the book, I wasn’t sitting there going, “This farmhouse will have this effect,” but it is true that there’s horror to it. For me, it’s part of myth building. You have stuff like Stephen King’s Children of the Corn, which is certainly upsetting or disturbing, but there’s also romance to it. These communities harken back to a lifestyle that’s unfortunately being overtaken by something far more insidious.

The majority of the novel’s momentum comes from detailed accounts of the characters’ internal thoughts and feelings. What made you choose this style over a more traditional narrative?

In Alain Robbe-Grillet’s great novel, Jealousy, a big part of what drives the story is just the narrator describing the movement of light. It takes a while to realize that these descriptions are part of the narrative. To me, it’s interesting that you can satisfy that narrative agreement with the reader—the agreement that there’s a plot one can follow—while simultaneously approaching that concept in such a way that it almost breaks that agreement.

So you wanted to play with that?

I think maybe a little bit. There was this mondo-style film that pretended to have real death in it. I think the film was called Snuff, or something equally sort of lurid. I just wanted to imbue parts of the book with a similar concept, this idea that you know something’s going on in the barn house, and it can’t be good. When I was working on the book, I asked John Hodgman to look at it. He said, “You know, it’s really good, but you have to pay the reader back.” It might sound silly, but without that suggestion, I suspect I would have just been drawing the curtain throughout the novel without offering that payoff.

There’s a cult similar to the Worldwide Church of God (now Grace Communion International) that plays a pretty large part in the book’s plot. Have you always been interested in fanatical belief systems that try to position themselves as religious alternatives?

As a kid, I would hear about cults from my friend Joe. He would tell me about brainwashing techniques and the like. This was back in the day before everything was immediately searchable, so all you could find on cults or cult practices was what your friends told you. I mean, there were some books, but they were dry. Now, you can go online and find out about them from every angle. In those pre-internet days, you’d hear a weird anecdote and think, This could be true, but maybe it’s not. Once I started figuring out what the book was going to be about, I remember getting excited about the idea of having a cult involved. I remember sketching in notebooks and just figuring out some of these questions I asked as a kid.

As a writer of both fiction and lyrics, how do you decide whether something is a story for a song or demands a longer life? Does one inform the other?

I can tell you it isn’t a situation where I sit down at the piano or with a guitar, start working on a song, and realize it’s a book. This concept—lovely as it is—has never happened to me. I started out writing poems that I spoke over music, and people seemed to like them enough. Actually, the song “Going to Alaska” was a poem on the first tape I made. Eventually, it occurred to me that it might be worthwhile to treat these like songs, and once I did, people seemed to like it.

So are lyric writing and novel writing mutually exclusive? In other words, do they take different types of creativity, or is it more about timing?

That’s a hard question. Creativity isn’t accidental, but capricious. However good a record gets, it’s never quite as good as when the first mix was done and everyone heard it together fresh. I don’t think that state has a form, but the form can take on different states.

Eric Farwell is an adjunct professor of English at Monmouth University and Brookdale Community College in New Jersey. His writing has appeared in print or online for Esquire, Salon, The Kenyon Review, The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, The Village Voice, and Vanity Fair, among others.