There is something about the Brontë sisters that is enduringly fascinating, something about their strange, gifted, and woefully abbreviated lives (none of them lived to forty) that reads like the stuff of myth. Perhaps it’s the combination of great personal privation and great artistic willfulness, the mixture of geographic isolation and literary renown, that lends their story an elemental note of warring forces both within and without. To think of these three motherless and conspicuously inbred young women—Charlotte, Emily, and Anne—living off in a parsonage on the Yorkshire moors together with an eccentric curate father and an alcoholic brother, in a Victorian climate that was unconducive to the creative aspirations of the female gender, and yet all the same producing a clutch of game-changing novels (Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey), is to wonder at the ways in which character and imaginative vision can triumph over circumstance.

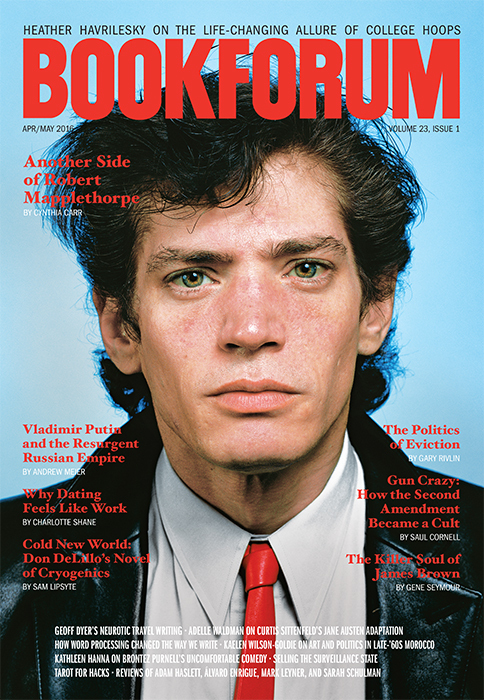

Among the bevy of books about this compelling family that have come out in recent years, there have been Juliet Barker’s heroically researched 1997 biography, The Brontës: A Life in Letters, and Lucasta Miller’s The Brontë Myth, published in 2004. Miller’s gracefully written and wonderfully entertaining account—or “meta-biography,” as she calls it—reexamined the ways in which the Brontës’ “lonely moorland lives” underwent a process of mythification even before Charlotte, the last sister, died in 1855. This “beguiled infatuation,” as Henry James put it, began with Elizabeth Gaskell’s landmark Life of Charlotte Brontë, which Miller describes as “arguably the most famous English biography of the nineteenth century” and one that “set the agenda which would turn the Brontës into icons.” Gaskell’s book was published in 1857 and became an immediate sensation; if not quite an authorized version, Gaskell’s was close to hagiographic, playing up her subject’s “womanliness” and her noble penchant for “self-denial,” rather than the more fiery romantic and intellectual passions that also ruled her life, and that have been brought to light by later biographers.

Charlotte, of course, is the Brontë who energetically saw herself and her more reclusive sisters into print (under male pseudonyms, originally) and about whom the most is known. The only one of the sisters to marry, she was in the early months of pregnancy when she died just short of thirty-nine. Given the complexity of her personality, especially its singular mix of abjectness and scrappiness, Charlotte is a natural lure for life-writers and has been the subject of periodic biographies since Gaskell’s effort to create a “woman made perfect by suffering”; these have included works by Winifred Gérin (1967), Rebecca Fraser (1988), and Lyndall Gordon, whose eloquently fleshed out Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life (1994) proposed to show how Charlotte’s habit of self-effacement was a role, one “designed to obliterate, for public purposes, the woman of passion and the volume of her utterance.”

Now, more than twenty years later and timed to coincide with the bicentennial of her birth in April, we have yet another retelling of Charlotte’s story in Claire Harman’s Charlotte Brontë: A Fiery Heart. The intervening years have seen the publication of all of Charlotte’s extant letters, which provide a gold mine of insight into her state of mind at various times, perhaps never more revealingly than when she wrote her friend Ellen Nussey (who, for all her timidness, refused to burn Charlotte’s letters, although she was exhorted to by Charlotte’s husband, who described them as “dangerous as Lucifer matches”) a few weeks into being married: “I know more of the realities of life than I once did. I think many false ideas are propagated—perhaps unintentionally. I think those married women who indiscriminately urge their acquaintance to marry—much to blame. . . . It is a solemn and strange and perilous thing for a woman to become a wife. Man’s lot is far—far different.”

Harman, who has written biographies of Fanny Burney, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Sylvia Townsend Warner, brings to her venture a lively style and an incisive mind. She comes without intellectual agenda other than her own curiosity; her life of Charlotte doesn’t offer a brand-new perspective so much as a subtle shift in our understanding of this “little woman,” as her contemporary William Thackeray called her. In the process of conjuring up a Charlotte animated by a zeal to write as well as by intense feelings of love and desire for Constantin Heger, the married professor she studied with in Brussels and eventually fictionalized in both Shirley and Villette, Harman infuses her with an intriguingly modernist spirit. She also contrives to understand how a woman so beset by anguish in life was able to deploy her sorrow and rage to creative ends, spinning her own childhood and its “tragic losses” into gripping tales. “Charlotte Brontë was essentially a poet of suffering,” Harman observes; “she understood every corner of it, dwelt both on and in it. In life, this propensity was a chronic burden; in her art, she let it speak to and comfort millions of others.”

Harman’s biography begins dramatically, almost cinematically, in medias res, with a brief prologue dated September 1, 1843, in which a twenty-seven-year-old Charlotte is stranded during a vacation break at the girls’ school in Brussels where she is “an unpaid student-teacher.” It is her second year at the Pensionnat Heger—her first year there had been shared with Emily—and she is on the verge of something akin to a breakdown, having just realized that her love for Heger, the headmistress’s husband, is unrequited: “And now the man she considered her soul-mate is pretending that she is nothing special to him at all.”

Although Charlotte, the daughter of a Protestant minister, has been raised to resist Romanism—“she has been brought up to pity Catholics and to fear them”—she finds herself kneeling at the confessional grille in the city’s gothic church. The “solace” provided by this “moment of freedom” would pave the way, according to Harman, for her eventual escape into writing. “Her experience in Ste-Gudule gave her an idea not just of how to survive or override her most powerful feelings, but of how to transmute them into art.” In Jane Eyre she gave vent to these feelings through her identification with the “poor, plain, overlooked governess” who is the novel’s unconventional heroine—and whom she suffused with an incalculable authority, standing in for all who feel burdened by their plight.

Harman also begins weaving in what will prove to be an important thread in her portrait of Charlotte, which has to do with the novelist’s ingrained sense of herself as resolutely unattractive: “She looks in the mirror and sees, with ruthless clarity, a catalogue of defects; a huge brow, sallow complexion, prominent nose and a mouth that twists up slightly to the right, hiding missing and decayed teeth.” Despite living in less harshly looksist times than our own, and despite being the recipient of two marriage proposals before finally accepting the hand of the enigmatic curate Arthur Bell Nicholls, Charlotte was deeply bothered by her ostensible lack of feminine charms—enough to have caused her publisher, George Smith, to observe that she had “an excessive anxiety about her personal appearance. But I believe that she would have given all her genius and her fame to have been beautiful. Perhaps few women ever existed more anxious to be pretty than she, or more angrily conscious of the circumstance that she was not pretty.” Even the worshipful Gaskell would, on meeting Brontë, take note of a certain undeniable homeliness, commenting that she was “altogether plain; the forehead square, broad and rather overhanging.”

After the prologue, Harman moves back into a more conventional narrative, filling in the lineaments of an oft-told, in many ways hair-raising story; even though the details are familiar, she presents them with polish and dispatch, pausing to suggest an alternate view here and a dissenting opinion there. We learn, for instance, of the literary bent of the siblings’ forceful and upwardly mobile Irish father, who rhapsodized about the “real, indescribable pleasure” of writing in an introduction to a collection of his poems. (He also wrote a novel and a kind of self-help book avant la lettre: The Cottage in the Wood; or, the Art of Becoming Rich and Happy.) Patrick Brunty (he changed the spelling to the more elegant Brontë as a young man) was the oldest of ten, born in “a two-roomed thatched cabin with a mud floor and rough-cast walls”; he catapulted himself to Cambridge and became an ordained priest at the age of thirty, establishing a reputation for being “an eccentric outsider” along the way. After a broken engagement he successfully courted Maria Branwell and the couple had six children in quick succession. In 1820 the family moved to Haworth—“a strange uncivilized little place,” as Charlotte later characterized it, set amid eight miles of moors and Yorkshire neighbors who cultivated a spirit of “surly independence.” Aside from attending church for Patrick’s “robust sermons” on Sunday, the family kept mostly to themselves. “There is no record,” Harman observes, “of any one of [the children] making friends with children from the village, and, on one occasion, when they were invited to a party, they stood around like aliens, utterly at a loss as to what to do.”

Maria died of cancer shortly after the move to Haworth, leaving her offspring in the care of her spinster sister, Elizabeth, and their quick-tempered father. (Harman brings up without fully resolving the ominous anecdotes about Patrick Brontë’s “volcanic” temper, suggesting that he had an iron will that first his wife and then his daughters learned to accommodate.) In any case, it was in the company of one another, in a parsonage that abutted a graveyard and looked out from the back onto the moors, that the genius of his four surviving children began to show itself (the two oldest girls, Maria and Elizabeth, died at the ages of eleven and ten, having been taken ill with tuberculosis at Cowan Bridge, later condemningly depicted by Charlotte as Lowood School in Jane Eyre).

Harman is excellent on the Brontë juvenilia, which was a natural outcome of the girls’ imaginary games, inspired by their brother Branwell’s collection of toy soldiers. Branwell and Charlotte began to produce a series of tiny magazines, filled with miniscule writing, “squared off to look as much as possible like print,” in inch-high booklets bound with thread, to document their characters’ adventures. These doll books included poems Charlotte wrote with Branwell as well as dramas and romances; they would eventually contain the invented worlds of Angria and Gondal. “The content of the ‘juvenilia’ was never juvenile,” Harman astutely notes; “the amount of it was phenomenal, and the work continued well into adult life, composed concurrently, in Emily’s and Anne’s cases at least, with published work.” She goes on to speculate that the “alternative reality of her Angrian fantasies . . . and her journal fragments of these years” suggest that Charlotte may have used opium (which Branwell became addicted to) to reach her “visions,” despite her denial to Gaskell of ever having touched the drug.

Harman is equally good at evoking daily life at the parsonage, where Tabby, a village local, was the one full-time servant, later described by Charlotte as boiling the potatoes “to a sort of vegetable glue,” and the girls passed some of the time in sewing and other household duties. (Although the girls had their share of lessons with Patrick, “intensive study of the classics” was Branwell’s domain.) She also provides a close-up of Charlotte’s fast friendships with two other girls she met at the Roe Head School, where she returned as a teacher. (Her sister Emily, on the other hand, seems to have been an unqualified loner.) During this period the nineteen-year-old Charlotte sent a poem she had written along with a somewhat overheated letter to Robert Southey, the poet laureate, requesting his opinion of her writerly worth. Southey’s answer—with its now-infamous proviso that “literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life: & it ought not to be,” adding that “the more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it”—chastened but did not quash Charlotte’s dreams for herself. Harman observes that the tone of her reply “rides the line between sarcasm and sincerity”; Charlotte concludes her letter thusly: “I trust I shall never more feel ambitious to see my name in print; if the wish should rise, I’ll look at Southey’s letter, and suppress it.”

The main thrust of Harman’s biography endeavors to show how this most self-doubting yet obdurate of young women turned her emotional vulnerability and anxieties about her place in society as a fiercely passionate but plain Jane into a new kind of literature, one that forged a candid and poignant female voice of unaccountable power, telling of childhood loneliness and adult longing. Charlotte’s thwarted relationship with Heger, which Harman attributes more to a cultural misunderstanding than to deliberate cruelty, would eventually lead to the triumph of Villette, featuring “a disturbing, hypersensitive alter ego, a ticking bomb of emotions called Lucy Snowe.” The novel appeared to mostly laudatory reviews, although critics also found Charlotte’s focus on her heroine’s fierce sexual need disturbing, with no less an authority than Matthew Arnold decrying the novel for its “hunger, rebellion, and rage.” Harman deftly situates Charlotte at home among her siblings, and then takes us with her as she makes her way as a newly heralded author into society, despite a persistent unease about being in company, visiting London at the invitation of her publishers and meeting with some of the greats of the day. She dined more than once with Thackeray, who responded to her with intense curiosity and admiration for her “independent, indomitable spirit.” There is a wonderfully poignant scene in London when the appearance-conscious Charlotte goes to a fashionable painter for the first of a series of sittings to have her portrait done and is asked to remove “a wad of brown merino wool that had stayed on top of her head when she took her bonnet off”—which proves to be a hairpiece. The experience leaves her “mortified (to the point of tears).”

The final chapter of Charlotte Brontë is called “The Curate’s Wife” and takes up the writer’s last years and her mysterious marriage. Harman writes with her usual attentiveness to the surrounding details—a bout of mercury poisoning, the day-to-day writing of Villette, her “most explicitly personal” of books—while keeping her eye on emerging developments. She notes that, since the deaths of Emily and Anne, and despite her new friendships (with Gaskell, among others), Charlotte’s “essential loneliness seemed to have hardened and grown.” Then comes the whole curious matter of Patrick Brontë’s assistant, Arthur Bell Nicholls, who fell in love with Charlotte; this reality seems to have dawned on her slowly and rather distantly, and to have put Patrick, who thought Nicholls an “unmanly driveller,” into a state of near apoplexy. Although Nicholls initially submitted to Charlotte’s lack of encouragement by leaving the parsonage for another post, he renewed his suit a year later and was met with a different response. Lest one imagine that romance was afloat and beating its wings, Harman asserts that Charlotte’s “change of heart towards Nicholls, or rather towards marriage with him, had an air of calculation about it, of assessing what her options were in a changed landscape.” Whatever the reasons, Charlotte overrode her father’s resistance (among other things, Patrick suspected Nicholls of being a gold digger) and became engaged, sounding coolly unenamored in the description of her feelings to her friend Ellen: “I am still very calm—very—inexpectant. Providence offers me this destiny. Doubtless then it is the best for me.” She got married in an “unshowy white muslin dress” at eight in the morning. The service was attended by very few people, as she wished.

Although Charlotte’s feelings for her husband deepened during the short months of their marriage, Harman comments that “it was hardly . . . the passionate meeting of ‘true souls’ that her novels—and her sisters’ novels—blazoned as the highest goal of the emotional life, and the birthright of every free-spirited woman, regardless of birth, class or looks. Charlotte Brontë had, in some respects, given her imaginative life over to her readers for them to foster and enjoy; she had found she couldn’t live it herself, only write it.” With this biography, Harman furthers our understanding of Charlotte’s art and life, revealing not only how her experiences and novels drew on each other, but also how they diverged. A Fiery Heart is a welcome and clear-sighted addition to a growing literature, one that respects the impenetrable mysteries that still cling to the female scribes of Haworth while offering a plausible perspective on what made them into quiet revolutionaries of the nineteenth-century novel.

Daphne Merkin is the author of The Fame Lunches: On Wounded Icons, Money, Sex, the Brontës, and the Importance of Handbags (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014).