Even in a decade not wanting for political weirdness, one of the weirder aspects of the past ten years has been American empire’s guilty conscience with respect to itself. On the campaign trail, both our current and our previous president complained about imperial overreach, about “stupid” wars that cost billions of dollars and weren’t winning the country any new friends. Then, in office, each president kept prosecuting those same wars, editing around the margins without fundamentally changing the scope of the country’s military presence around the world. On both sides of the aisle, our representatives mostly agree that America has to stop wasting money on unnecessary wars, while also mostly agreeing that all of these wars are vital to American security—bombs away!

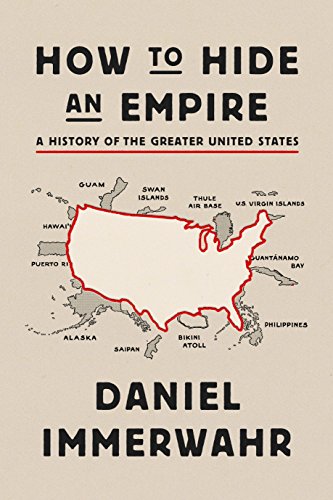

Some of the sharpest insights in Daniel Immerwahr’s new book, How to Hide an Empire, have to do with the long-running pedigree of this guilty conscience. The outline of the contiguous United States, the shape that most people think of when they hear the name, was only an accurate representation of the country’s borders for three years, between 1854, when the Gadsden Purchase was ratified, and 1857, when the US started collecting small islands throughout the Caribbean and the Pacific. Nevertheless, this outline persists as what Immerwahr calls the “logo map” of the country, covering up America’s overseas acquisitions and impeding mainland Americans’ ability to recognize Puerto Rican victims of Hurricane Maria, to take one example, as American nationals. Immerwahr puts this and other stories about America’s overseas territory at the center of US history, and as a result his book has caused some excitement among people who study and write about empire professionally. This isn’t the kind of perspective one usually finds in mainstream histories of the United States.

The book is divided neatly in half. The first half documents empire in the traditional sense, when the US has acquired territories, mostly to exploit the raw materials located there, and ruled them via occupation. This phase of empire began with the country itself. Just two months before Britain formally granted independence to the US in 1784, Virginia ceded its claims on land north of the Ohio River to the federal government. “From day one,” Immerwahr writes, “the United States of America was more than just a union of states. It was an amalgam of states and territory.” He follows the colonial settlers westward across the continent, through a series of imperial conquests of the many sovereign American Indian nations that stood in their way, and then over the water to new lands: Guam, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and dozens of tiny, uninhabited islands in the Pacific, from which nitrogen-rich bird guano could be gathered for use as fertilizer. The country’s record up through the early twentieth century is one of continuous expansion, carried out at gunpoint whenever necessary.

Immerwahr is strongest as a kind of phenomenologist of empire, tracking down and dusting off the small artifacts of American history that only got lost or discarded in the first place because they were incompatible with the country’s self-image as a beacon of self-determination for all. As an example, Immerwahr notes that until 1898 almost nobody called the United States “America.” He found just one use of the term per decade in “all the messages and public papers of the presidents—including annual messages, inaugural addresses, proclamations, special messages to Congress, and much more—from the founding to 1898.” What changed in 1898 was that the Spanish-American War ended with the Treaty of Paris, as a result of which Spain ceded the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the US. Before that, people had mostly called the country the “United States” (or “the Republic” or “Columbia”), but suddenly that was no longer an accurate description. The word America now began to appear in patriotic songs: “God Bless America” and “America the Beautiful” were both written after 1898. “America” is, specifically, the name of an empire.

If Americans today know almost nothing of their country’s imperial history, they could not be counted on to know about it at the time, either. Empire was the main issue of a presidential election just once, in 1900, with William McKinley in favor and William Jennings Bryan opposed. The subsequent absence of public debate allowed empire to move silently through American life and culture like an absent root in music, the unplayed note around which the other chords revolve and harmonize. Immerwahr mentions the 1928 book Coming of Age in Samoa, which turned Margaret Mead into the world’s most famous anthropologist. “It is entirely possible to read Coming of Age,” Immerwahr writes, “without realizing that the ‘brown Polynesian people’ she describes encountering on ‘a South Sea island’ are U.S. nationals.” Even more striking is the story of the World War II–era GI who, walking down the street in Manila, is shocked to hear a Filipino boy speaking fluent English. The boy explains that the US instituted English in the schools after colonization, which “only compounded the GI’s confusion,” Immerwahr writes. “He thought he was invading a foreign country.”

The book’s second half narrates the transformation of American empire that occurred after the Second World War, as the US assumed its place as world hegemon. Immerwahr is less successful here because he runs into the limits of his anecdotal approach. He argues that the original version of US empire, which relied on the control of geographical space, was challenged by three postwar developments: the increased use of synthetic chemicals, which decreased America’s reliance on raw materials that could often only be found abroad; technological advancements in travel, communication, and industrial standards, which allowed the US to maintain a global presence without having to set up occupations everywhere; and American military bases, some eight hundred of which now dot the globe. He doesn’t quite say what the bases are for, but he does mention that quite a few non-Americans have minded their presence in their home countries, among them Osama bin Laden.

Immerwahr refers to these developments as “empire-killing technologies,” which is an odd choice of phrase, because he doesn’t actually believe the US abandoned an imperial way of life. Rather, he thinks it traded in an older model of “colonial empire” for what he calls “pointillist empire,” one based on hundreds of tiny territorial holdings (the military bases) in lieu of a handful of large ones. This half of the book contains dozens of interesting examples of these empire-killing technologies in action (over the course of the Second World War, the US successfully synthesized away its dependence on naturally produced silk, cotton, wool, tin, copper, and rubber, among many other materials). But it doesn’t answer the basic question that would prompt someone to read the book in the first place: Why does America have a fundamentally different relationship to the rest of the world than any other country? Immerwahr’s account has observational value but little explanatory power. He never acknowledges or analyzes the engine of postwar American empire, which is the country’s self-assigned mission to keep the world safe for capitalism. An unrealized awareness of this mission suffuses the book’s second half, especially in the discussion of industrial standards (you want everyone’s screws to be the same size so that you can buy and sell industrial parts anywhere in the world). But the actual word capitalism appears only once in more than four hundred pages, and it’s in a quote from someone else.

American empire in its current form is an outgrowth of the capitalist system. In the centuries preceding the Second World War, it was the great European powers that implemented capitalism’s expansionary mandate, colonizing some 80 percent of the earth in pursuit of raw materials and geopolitical supremacy. That colonial system disintegrated over the first half of the twentieth century, in large part due to the resistance of the colonized. But if what used to be called the third world no longer accepted permanent physical occupations by foreign powers, it could still be made to allow the penetration of foreign capital into its economies. American empire has spent the past half century prying open these parts of the world with a crowbar and then installing military bases to guard against any backsliding. It makes sense that the region in which US military involvement is the most intense, the Middle East, is also home to the world’s largest reserves of a crucial raw material that hasn’t yet been replaced by a synthetic chemical substitute.

Because he never accounts for the fundamental economic motivations behind empire, Immerwahr also fails to mention even once the greatest empire-killing technologies of all: the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization. The IMF, for instance, has played a major role in world economics since the crisis of capital overaccumulation in the 1970s, forcing states to slash worker protections, devalue their currencies, reorient their economies toward exports, and sell off their public assets on the international market in exchange for loans. Because the governments that hold these assets—railways, infrastructure, education systems—are in crisis, the assets get sold at rock-bottom prices, and within a few years or a few decades, when things are back to normal, foreign investors have realized a handsome return on their investment. This is the substance of American empire in its present form: economic intervention around the world on behalf of capital investment, plus military intervention in cases where foreign governments aren’t sufficiently compliant. America didn’t take on this level of global responsibility on behalf of all the world’s capitalist nations out of altruism. The US has the highest levels of consumption in the world, consistently running a trade deficit since the 1970s, and it’s probably not an exaggeration to say that sustaining this debt-funded consumption is a condition of American social peace. He was criticized for it at the time, but there was a good reason for President George W. Bush to encourage Americans to go shopping in the wake of September 11, during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq. As the military prepared to defend America’s imperial privilege around the world, Bush was telling us to enjoy its fruits.

Immerwahr spends less than ten pages discussing the war on terror, and much of that is focused on reiterating the idea of imperial pointillism. “The enemy in this style of warfare was not a country,” Immerwahr writes of drones, “but a GPS coordinate,” a sentence that is both grating in its lack of curiosity about the political implications of such warfare and also false: The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were aimed at overthrowing the governments of nation-states. Empire, as a subject, requires exactly the kind of geopolitical thinking that is missing from this book. Immerwahr seeks refuge in the details, but without an overarching idea about what the military bases and interventions are for, all you’re left with is a picture of a bunch of different places on a map.

Richard Beck is a writer and editor at n+1.