AN OVERPOWERED REBEL casts his eyes up in terror at the warrior ripping him away from his grieving mother. Survivors on a corpse-covered raft at sea, dispatched by a vicious colonial government and abandoned by their superiors, stretch desperate hands toward the horizon, where a rescue may or may not be approaching. A peasant rebellion successfully throws off exploitative foreign rule, but when it threatens the power of the local nobility, the squires hack its leader to pieces. In Paris, the directionless vanquished of the Spanish Civil War try to sleep in their newfound disunity on a liberal banker’s floor. An orchestra of imprisoned anti-Nazi fighters coolly face their haphazard bureaucratic executions, while one begs for her life.

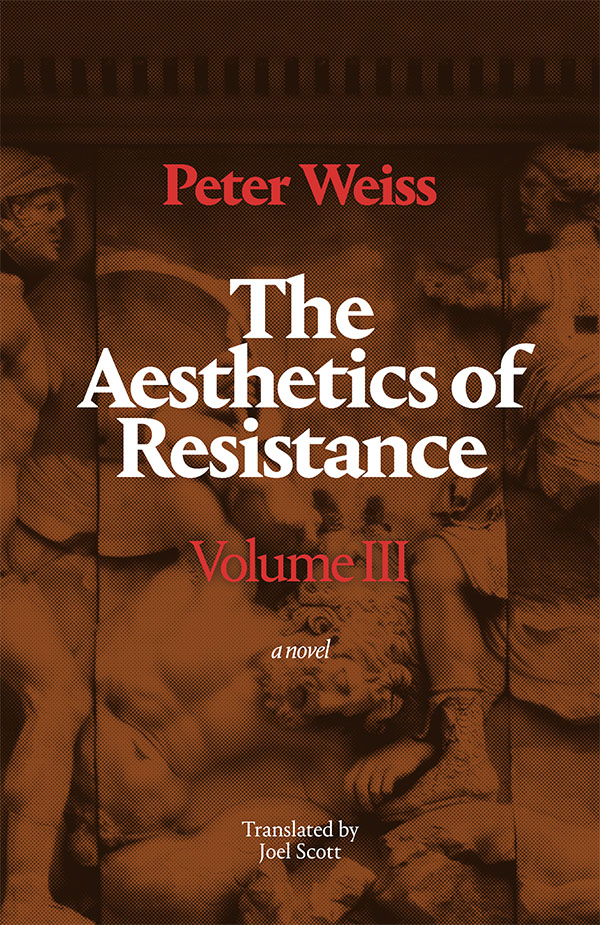

Staring down these harrowing images of defeat, and making sense of them with other people, is the project Peter Weiss gives us in The Aesthetics of Resistance, now fully available in English for the first time with the publication of its final volume. Set in Europe from 1937 to 1945, Weiss’s three-part, 1,000-page novel, originally published between 1975 and 1981, follows the trajectories of people working across the broad spectrum of the left to overturn that era’s fascist regimes. Every character in the novel, except the fictionalized Weiss-adjacent protagonist and his parents, actually fought this war. Many, though not all, died in the process. As they chase possibility across the continent and conditions deteriorate under their feet, they think together as much about their present as about the past that made it possible, seeing what sense they can make out of histories of frustrated struggles for freedom. And they return compulsively to pieces of art—many politically unradical and formally traditional—that shaped their consciousness, that help them understand and enable others in a period of suffocating repression.

Given the lethal urgency of Weiss’s political object, it’s a strange choice. Who cares about a Greek frieze, one that the Nazis might even have made into evidence of their glory, when the foundations for sense itself are under attack? Why scrutinize fascism at an angle, and why stare into the abyss of these tableaux of half-completed destruction when everything around you is on fire? If “resistance” means the will to fight back rather than the credible plan to win, and if “aesthetics” is a luxury that can embarrass even the credentialed among us, why would people looking to completely redirect the free-fall of history spend time on a book like this?

Born in Berlin in 1916, Weiss was barely an adult when his family fled the Nazis in 1935, and spent most of his life in exile in Sweden. Partly Jewish, but with relatives who had joined the perpetrators, Weiss was haunted all his life by the two roles he narrowly escaped. He came to both writing and radical politics in his forties after a sluggish career as a painter, and when he did, he made up for lost time. Fundamentally preoccupied by questions of what can happen when people rehearse historic struggles as they face their own, he dragged audiences through scenes that develop our capacity to think. His works barrel forward, spring-loaded with productive doubt and all-sided inquiry while never cheaply dismissing the imperative to act, and act together. Brecht and his methods are in evidence everywhere in Weiss’s work, and like Brecht, Weiss forces you to ask how the crisis you’re reading about could have been prevented, how it could still be transformed, and what it means for you right now. Weiss focused his attention over and over again on horror and violent transformation—the French Revolution, the Holocaust, the wars of liberation in Vietnam and Angola; in this sense, he straddles many of the same formal and thematic problems of representing the complexity of calamity as his admirer, filmmaker Harun Farocki, who shot a documentary on Weiss’s process researching and writing The Aesthetics of Resistance before it was even finished. Through teaching us to think collaboratively about scenes of devastation and vast social upheaval, Weiss wants us to learn a method for scanning for the resources available to remount the fight when gazing on a catastrophe that keeps piling wreckage. “When will you learn to see?” asks the radical Red priest Jacques Roux in Weiss’s most famous play, Marat/Sade, in a question that’s more than an accusation: “When will you learn to take sides?”

And not just when—how? In the first volume, Weiss furnishes a haunting, powerful metaphor for the work that The Aesthetics of Resistance makes possible. His protagonist has traveled from Berlin to Republican Spain to fight in the International Brigades against Franco. As the fascists gain ground and the brigades are disbanded, the narrator, waiting to ship out, consults a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which dramatized the fascist bombing of the Republican town in April of that same year.

There was a reminiscence of Medusa, from whose body Pegasus sprang. Her dreadful face with the petrifying glance was recognizable both in the horse’s head and the warrior’s. Turning away from the Gorgon, catching her grimace only in a mirror, Perseus had killed her, and this evasion was also inherent in Picasso. . . . Perseus, Dante, Picasso remained unscathed, handing down what their mirror had captured, the head of Medusa, the circles of the Inferno, the blasting of Guernica. . . . The catastrophe descending here on the faces and bodies contained dimensions that we could not grasp. The shapes and gestures flattened by air pressure were stamped into the pictorial wall by a light that no eye could endure. Any attempt at directly explaining the depiction would lead to extinguishing the work.

Weiss treats Picasso’s painting of fascist carnage like Perseus’s polished shield as he fought Medusa. You can’t look the nightmare dead-on, he says, it won’t do what you think it does. The overwhelming scale of the destruction will freeze you in your panic, and you won’t even see what you need to see. Looking at catastrophe backward, in a mirror and at a remove—Weiss implies that this way of seeing can help us learn both to take sides in the fight and also to understand what to do next, whenever and if ever we might find ourselves facing this scale of horrors again. We don’t need to tell you that these questions are, fuck’s sake, not hypothetical or abstract for any of us.

TRUE TO HIS PROMISE, Weiss makes no attempt to represent the nightmare in any straightforward fashion. The overall narrative arc follows the protagonist and his comrades from Berlin to the fight in Spain, then Paris, Stockholm, and back to Berlin, while his parents’ trek through Poland and the Baltic states provides a window into the deportation of Jews, political dissidents, and other sacrificed people into the death camps. But the main action of the fight against fascism takes place offstage. The characters mostly wait for news, crowding around a radio, tending to their day-to-day tasks, acting on rumors, decoding messages, contending with doubt, debating each other, relaying memories, and boiling the kettle as bombs go off outside and countries fall to the Nazis. As Joel Scott, who painstakingly translated volumes II and III, regularly emphasizes, much of the text is reported to the reader second-, third-, or fourth-hand from its original source: the narrator may go for a walk with an older comrade who recalls a conversation with the left cultural organizer Willi Münzenberg about meeting Russian revolutionaries in Zurich during World War I, and yet the characters put these metabolized insights to work in their own time. In this sense, The Aesthetics of Resistance is mainly a novel about consciousness—about how people draw on the interpretive tools they and their comrades have developed to make sense of what kind of hell they’re up against, how it got to be that way, and how they can stop it.

Over the course of the novel, these windows of information narrow considerably as the bottom falls out. The first volume, with its horizon of hope in the Spanish Republic and Soviet Union, feels expansive in comparison to the distantly felt disasters of the second, during which World War II breaks out, the Soviets sign the Non-Aggression Pact, and the Nazis extend their territorial stranglehold. The third is breathless, claustrophobic: almost all of the political activity here takes place through small underground cells, as the characters transmit messages from their hideaways, and relentlessly practical resistance fighter Charlotte Bischoff returns concealed in the ballast tank of a ship to hide among her Nazified compatriots.

If this strangling of information is one sign of the coercive forces that the characters contend with, Weiss asks us to pay close attention to how anybody assembles the will and resources to regain ground in the fight. Here, too, he finds a surprising resource in people hashing out complex aesthetics. The artworks that transfix his and his characters’ attention become training grounds, history lessons, and transmitting stations for oppositional consciousness—extending politically well beyond the biographies and sympathies of the people who created them. In the Pergamon Frieze and its lavish depictions of the Olympian gods’ triumphs over the rebellious giants, Weiss’s characters uncover a vast material history of domination and revolt. In Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), they see the anguish of the defeated French Revolution, the horrors of colonial profiteering, and the barbarism of the restored Bourbon kings. Weiss makes particular hay out of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), which differently repressive French regimes of the nineteenth century repeatedly hid from public view out of fear the painting would inspire yet another revolution—although Delacroix himself “was closer to the bourgeoisie than to his heroes, he was ready to turn against the upheaval. . . . He had visualized a date, just as Picasso had done with his painting, a second of contradictory hopes.” The characters are invigorated by Dante putting his powerful, corrupt contemporaries in Hell. They see in Dada and Surrealism a cultural counterpoint to the revolution in St. Petersburg, and they debate what the political and cultural revolutions accomplished, and what they failed to.

In focusing your attention through the characters’ eyes on these visions, Weiss moves you beyond basking in the perverse relief of despair, or sitting back and cheerleading “the people’s” inevitable will to fight back. Instead, he’s showing one method for how people under extreme duress arrive at the habits of mind and heart that keep them in the fight and force them to learn from past defeats. There’s something in this process that Ruth Wilson Gilmore emphasizes when she notes how people over time and place look to past moments of struggle to make new and vivid sense of their fights for a life worth living—what Gilmore calls the “selection and reselection of ancestors.” In thinking with furious drive and weary patience how to finish for real these faltered, scattered gestures at liberation, Weiss’s characters find surprisingly deep repositories for radical thought and action, under conditions no one would ever choose. The artworks transmit to them over decades and centuries what no actual survivor had the opportunity to say, and enable them to develop, through protracted and fierce debate with each other, the supple, dynamic, detail-oriented consciousness that they find they have no choice but to repurpose for their fight ahead.

THE NARRATOR, a worker turned both writer and fellow-traveler, agonizes throughout the novel over how he can adequately capture in writing the complex process of thinking he’s learning along the way: how to tangibly reason out the dynamics of a reality in violent motion in all of their contradictions. Weiss’s move here is almost campy in its clarity, as he explains third-hand some of the formal acrobatics he’s been subjecting his readers to. Beneath a steadily forthright and curious tone, Weiss smashes passages ranging widely in genre and content into each other: exhaustive inventories of figures in paintings collapse into centuries-long histories of the roiling class societies that made a particular image possible; accounts of disturbing hallucinations and meditations on the psychic drives motivating political action inconclusively frame histories of a century of splits among Swedish social democrats; the editor of the party newspaper defiantly ventriloquizes the styles of arrested comrades while Brecht’s company retools a fifteenth-century rebellion into a teaching play about the factions of the Swedish ruling class making peace with the Nazis; retellings of mundane days in the underground burst into fiery but unsettled debates over the relevance of formal experimentation to people too tired from working or terror to read. These collisions provide an opportunity to evaluate each new kind of text by the reading habits of ones we just slipped out of—collapsing divergent sight lines into something more unstable but also more usable than a clean synthesis.

Scott’s extensive work on this translation pays off powerfully, making the book’s challenges as readable as they can be in English without sacrificing key conclusion-suspending moments Weiss’s German kept unbearably taut in their incommensurate completeness. And it’s a good thing, as this is how Weiss trains his audience in a form of political thinking: he forces us to turn over problems from previously inconceivable angles like we’re casing a house, trying to discover entryways that might open up if we loosen habits of seeing and let a new perspective emerge. Through demonstration rather than argument, Weiss encourages a kind of ecumenical expansiveness required to think with people who’ve come to different conclusions, and nevertheless not give up the necessity to engage, investigate, persuade, and move, with sturdiness to guide decisive action when needed and without the brittleness that cracks on contact with a changing reality or an off-program observation.

The book’s regularly staged political debates—on splits among left parties and broader democratic forces in differently constituted fronts over strategy, on the political and cultural vehicles that could shift the terrain to slow the disaster and reverse its advance, on the nature of fascism and how it made its nightmarish gains, and on what barricades could still be thrown up against it to expand the realm of emancipation—are inconclusive. In the course of the book’s onslaught, we hear the narrator’s father defend his decision, as a participant in the failed 1919 revolution in Germany, to return once more to the fold of the ruling Social Democratic party that helped crush it; we see the different left factions in Republican Spain maintain practical unity out of necessity in the Popular Front against Franco while still bubbling with skepticism for each other’s theory of change; we return compulsively, traumatically to moments in Weimar history where reasonable people made different assessments about whether to stop the advance of the Nazis by drawing on the strength of a broader front of fickle social factions, or by acting more forcefully with a narrower but sharper coherence, and how painful it is that both may have been right; we read the letters of arrested resistance fighters in Berlin before their executions as they fitfully forgive each other for revealing anything to the authorities. Even the most convincing arguments, rehashed with inverse winners hundreds of pages apart, come sown on all sides with doubt and reservations, and the reader comes to understand how many times people had to learn to operate through subtext—implication and complicity, rather than noble, risky, and impotent declarations—as they moved to build the power they needed to change anything about what was happening.

It’s not a parlor game, or complexity for complexity’s sake. It never is. Weiss’s characters are grappling with the live fact that kids they grew up with are killing others and being killed, ratting each other out to the police or at best to the Central Committee, losing their capacity to maintain the discipline of hope, getting swept up in the assault on thought, and surrendering the ability to imagine they share anything with the freshly dehumanized.

At this kind of crossroads, it’s not a luxury—in fact, it’s inevitable—to ask yourself these questions: How on earth do other people come to the conclusions that drive them to do anything or nothing? What seeds exist in that consciousness, even among those frozen in total despair or fascist venom or unstrategic rage or hypertrophied discipline, that could be repurposed to motivate action that could make a different life possible for all? How do we make sense of reasonable people with a common enemy who used partial information to make wildly divergent decisions under the kind of duress that people like us are only now beginning to be able to imagine?

Laying out other people’s agonizing decision-making alongside their nagging doubts and cramped habits of thought, Weiss trains us to develop the political theory of mind that we need in order to do what organizers everywhere are trained to say that we do: “meet people where they’re at.” There are no shortcuts around listening with patience and creativity to the reasoning that guides people either to act or to freeze, and to moving them to understand that they—and we—ought to take a different course.

THERE’S ANOTHER KEY ASPECT to the point Weiss makes by engineering disorientation as he hauls readers through the novel’s full sweep. The Aesthetics of Resistance drifts in and out of code names; pulls unannounced shifts in time, place, and perspective; packs pages with sparing punctuation and no paragraph breaks; carries on for pages of pronouns without a name; and launches you into what feels like an impossible array of fields for any one person to have even passing familiarity with. It’s almost as though you’re meant not only to feel what the characters are feeling, regaining their footing with every shift of who is who and what is known, but also to learn how to navigate such a world yourself, should the convulsions of hatred scramble the coordinates of our lives again.

And though you do have to do it yourself, you’ll find you cannot do it alone. Making sense of this book required the two of us working through patient, comradely, even loving discussion and transformative disagreement, relying at every step on other people and the things they know and know how to do. The breadth of the references in the book—dozens of characters, centuries of histories, entire galleries of works of art and libraries of literature, theoretical flights of the psyche and political economy—is so wide-ranging as to almost insist you read it with others. German trade unionists in the 1980s ran reading groups to see what they could make of it together. The series of cascading arguments into which Weiss hammers his research and writing opens us outward. Just like in Marat/Sade, Weiss in The Aesthetics of Resistance models dialectical thinking through productively frictive conversation, as steel sharpens steel: he forces us to take seriously both sides in political debates that we ourselves have no practical stakes in, but that we ought to learn something from and can only come to grips with by thinking generously alongside other people. Essentially, the book makes the reader surrender to the fact that you can neither understand nor change things all on your own.

It’s almost like Weiss wanted to prepare us, our ability to listen, to imagine, to stay rooted and stable, to trust, to be able enough to take collective action in the midst of a calamity. The book is a challenge, it’s training, but it’s not impossible. Neither is this moment.

If anything has become apparent in the flood of the last months, it’s how difficult but indispensable it is to learn how to function with other people with limited information, to put one foot in front of another as part of a larger effort without having the certainty of understanding what happens. The terror we face is designed to leave us feeling trapped in futility. Rehearsing what to do when lost and looking backward, thinking together about why any of us do anything, and figuring out what things we can do to reset the terrain—this is the whole point. The book is of course not going to be most people’s path to this, as people with different resources and traditions have always found ways to be effective, but it is a powerful one. If it sounds useful to you, find someone to read it with and make use of each other. It’s hard to believe this translation has arrived no later than now. And just in time.

Kay Gabriel is a writer, organizer, and the editorial director at The Poetry Project. Patrick DeDauw is a strategic labor researcher and geographer at The Graduate Center, CUNY.