Courtney Fiske

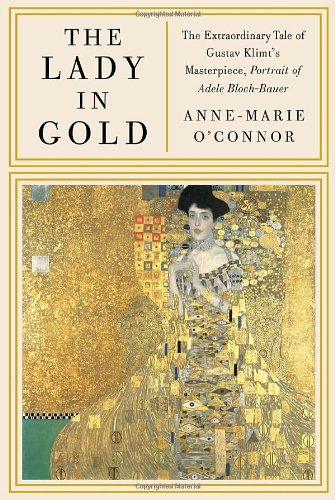

At its most romanticized, fin-de-siècle Vienna was defined by nihilistic revelry, fueled by an excess of booze, pastry, and existential angst. Yet by the time Austria was absorbed into Nazi Germany in 1938, this world had undergone a collapse more thorough than any in modern history. As if overnight, social distinctions entrenched since the Middle Ages became meaningless. Dynastic titles like “Habsburg” and “Auersperg” lost currency in a society now based on a single binary: Aryan or Jew. Washington Post journalist Anne-Marie O’Connor’s first book, The Lady in Gold, illuminates this cultural moment and its subsequent implosion through Gustav Klimt’s

Ha Jin’s writing shares something of his biography. Born in 1956 in northeast China, Jin volunteered in the People’s Liberation Army before venturing stateside in 1985 to study American literature at Brandeis University. Spanning four short story collections and six novels, his oeuvre confronts events in China’s recent past—the Korean War, the Cultural Revolution, and Tiananmen Square—head-on, with a bluntness that verges on deadpan. His prose has a similar effect to that of poetry: spare and unadorned, it traces, evokes, but refuses to spell out. This style befits the worlds that Jin renders: his historical vignettes are almost always Something is lost when tennis is televised. The blocky, overhead vantage favored by networks compresses the court and caricatures its occupants. The ball becomes a blur of fuzz and neon, often shot in histrionic slow-mo. Reduced to a series of zoom-ins and zoom-outs, the game congeals into a mass of grunts, moans, and commercials. Well-executed prose, by contrast, amplifies tennis’s inherent drama, probes its psychic interior, and reveals its resonances beyond the court’s 2,800-odd square feet. The following texts play with tennis in this expanded verbal field, exploiting those techniques of deceleration and dilation at which the written word remains