At its most romanticized, fin-de-siècle Vienna was defined by nihilistic revelry, fueled by an excess of booze, pastry, and existential angst. Yet by the time Austria was absorbed into Nazi Germany in 1938, this world had undergone a collapse more thorough than any in modern history. As if overnight, social distinctions entrenched since the Middle Ages became meaningless. Dynastic titles like “Habsburg” and “Auersperg” lost currency in a society now based on a single binary: Aryan or Jew. Washington Post journalist Anne-Marie O’Connor’s first book, The Lady in Gold, illuminates this cultural moment and its subsequent implosion through Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, a member of Vienna’s then-thriving community of affluent Jews. Moving from the painting’s creation at the turn of the century to its theft by the Nazis and the prolonged legal battle for its restitution, O’Connor skillfully filters Austria’s troubled twentieth century through the life of Klimt’s most beloved muse.

In this lost world of Mitteleuropa, life as a Jew was precarious. While wealthy Jews entered Vienna’s “second society” of industrialists and constructed elaborate palais on the Ringstrasse, Russian and Polish Jews fleeing pogroms crowded the Jewish ghetto on the banks of the Danube Canal: an area unaffectionately termed Matzoh Island. The rise to cultural prominence of Jewish families like the Rothschilds and Gutmanns fueled anti-Semitism in Vienna’s populist political scene, which was then epitomized by city mayor Karl Lueger, known to Hitler as “beautiful Karl.” Though Vienna’s most prominent Jews strove to assimilate into the mainstream—Freud is said to have strolled the Vienna Woods in lederhosen—popular bigotries excluded them from fully claiming Austrian identity.

Raised in a poor Catholic family on the outskirts of Vienna, Klimt enters O’Connor’s narrative in 1896, the year before he engineered the Secession, an exodus of nineteen artists and architects from Austria’s official arts academy, or Künstlerhaus. The movement rejected the Künstlerhaus’s derivative, realist style, beholden to the Old Masters and conservative benefactors. Led by Klimt and bankrolled by Jewish patrons, Secession artists made the case for a new art, or Art Nouveau, defined by expressive lines, saturated colors, and subjective forms. Their bid for aesthetic autonomy embodied the contradictions of the moment, its style poised between figuration and abstraction, its mood symptomatic of fin-de-siècle malaise and Freud’s contemporary revelations into the depths of the psyche.

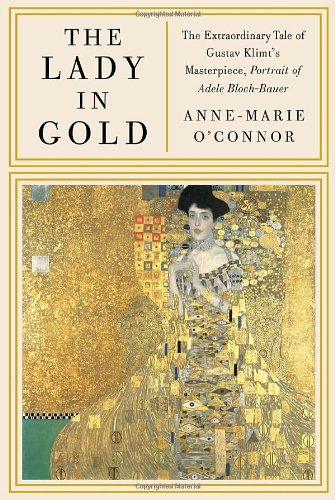

Debuted at the Kunstschau in 1908, Klimt’s Lady in Gold exemplified the aspirations of Vienna’s nascent avant-garde. Completed over the course of five years, Klimt’s portrait of Adele, cast before a mosaic of gold leaf, became an instant icon of the “new Viennese woman”: a Salome figure, at once regal and dissolute. As Klimt and Adele left no clues as to how they spent their time behind the closed doors of Klimt’s studio, the exact nature of their relationship remains unclear. O’Connor, however, calls attention to Klimt’s reputation for serial philandering and the naiveté of Adele’s husband, Ferdinand, a kindly man roughly twice her age.

Klimt died from a blend of Spanish flu and syphilis in 1918. Adele passed seven years later, still too young to see her world blown apart. O’Connor’s story, however, continues long after the deaths of these figures. Shifting the narrative focus to Adele’s niece, Maria Bloch-Bauer, O’Connor documents Hitler’s steady rise to power. Sweeping modernism (branded as a thoroughly Jewish phenomenon) aside in favor of a muscular and hyperbolically German art, the Nazis’ 1937 “Degenerate Art” exhibition codified Hitler’s Aryan ideal. Adele’s portrait, meanwhile, was seized under the pretext of Aryanization and became the property of Hitler’s regime. Hung in a 1943 exhibition under a new, nondescript title—Portrait of a Lady with a Gold Background—Adele’s Jewish identity was expunged, her personification of belle epoque Vienna an impermissible threat to the Reich’s racial dogma.

By 1945, O’Connor estimates that the Nazis had seized a staggering 20 percent of the Continent’s art. A single salt mine in the Austrian Alps housed Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, Vermeer’s The Artist in His Studio, Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, and over 6,500 other works. In the string of small complicities that sustained Hitler’s project, leading figures in Vienna’s art world concealed the provenance of these stolen pieces. After the Nazis’ defeat, reparations did not come easily to Jewish survivors like Maria Bloch-Bauer. Though Austria’s 1946 Annulment Act voided all wartime transactions, government officials retained Aryanized artifacts in the name of cultural patrimony and extorted “donations” from Jews eager to leave the country. Many Austrians also embraced a revisionist history: rather than a willing collaborator, Austria was the Reich’s first victim.

O’Connor’s narrative bears all the marks of a scrupulous reporter: pithy, fact-laden paragraphs, ample primary sources, and a commitment to telling all sides of the story. The book’s strength lies in the depth of its details, whether of Vienna’s concert halls or Hitler’s paranoid visions. Yet after the drama of the book’s beginning, its final chapters documenting Maria’s legal battle to reclaim her family’s Klimts seems anti-climactic. In 1941, Erich Führer, the Nazi-appointed administrator of the Bloch-Bauer estate, bequeathed The Lady in Gold to the Belvedere’s Austrian Gallery. With the war over, the Belvedere refused to relinquish ownership of the portrait, claiming that the terms of Adele’s will entitled them to the artwork, despite the illegitimate nature of its acquisition. O’Connor’s account of this near decade-long legal contest—involving modernist icon Arnold Schoenberg’s grandson and the US Supreme Court, and culminating in a record-breaking auction at Christie’s—lacks the fascinating history of the book’s earlier episodes. For a painting so tied up in Vienna’s past, there’s something heartbreaking about seeing Adele ensconced behind glass at New York’s Neue Galerie. But if the Nazis whitewashed Adele’s history, O’Connor’s book does the opposite, offering readers a nuanced view of a painting whose story transcends its own time.

Courtney Fiske is a writer based in New York.