Lauren O’Neill-Butler

Melissa Broder’s 2016 book of contemplative essays, So Sad Today, revolves around her chronic depression and the anxieties and illnesses that attend it. Exhilaratingly, she is willing to truly let it all hang out, charges of “narcissism” be damned. In one passage from the book, she discusses the “ocean of sadness” she was trying to block through therapy, antidepressants, and sundry other remedies. “I always imagined that something was supposed to rescue me from the ocean,” Broder writes. “But maybe the ocean is its own ultimate rescue—a reprieve from the linear mind and into the world of feeling.”

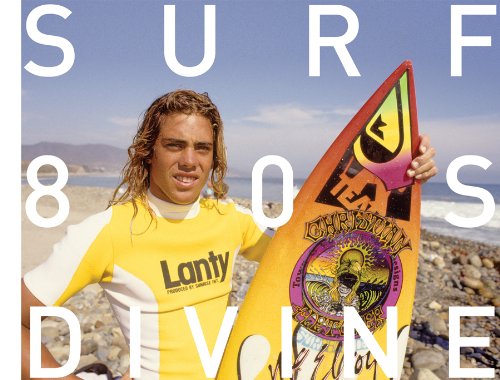

As brand-name gear, advertising, and competitive championships changed the look of surfing for the MTV generation in ways both brilliant and vulgar, it was a cruel (endless) summer for some. Sage surf photographer John Witzig spat, “This new generation has no experience of the laid-back hippy trip. Being cool is uncool.” (Was surfing ever uncool?) A new book by Witzig’s contemporary Jeff Divine, photo editor of the Surfer’s Journal, presents yet another point of view. A follow-up to 2006’s Surfing Photographs from the Seventies, Divine’s latest volume is from the 1980s and shot mostly on color-saturated Kodachrome 64 in Southern These books by artists—mostly painters—read like diaries. They reveal the successes and failures, highs and lows, of working in the late 1960s up through the ’80s. Rather than telling studio stories, the artists focus on art and life; some, like Lee Lozano, make a case for fusing the two, while others offer a subtle acknowledgement of and attitude of defiance against the “idiocy of painting,” as Gerhard Richter put it in his collection of writings The Daily Practice of Painting. The recent revival of these artists adds yet another layer of complexity, but their narratives speak to something larger: the

“I still believe in the power of words to change culture.” That’s Lin Farley, a writer and former reporter, who coined the term sexual harassment in 1975. Farley was teaching at Cornell University at the time and, after conducting feminist consciousness-raising sessions with students, discovered that every young woman in the group had been fired or forced out of a job after rejecting the sexual advances of a male boss. Eleanor Holmes Norton, then the head of the New York City Commission on Human Rights, invited Farley to a hearing on women in the workplace. Farley used the phrase, the