Melissa Broder’s 2016 book of contemplative essays, So Sad Today, revolves around her chronic depression and the anxieties and illnesses that attend it. Exhilaratingly, she is willing to truly let it all hang out, charges of “narcissism” be damned. In one passage from the book, she discusses the “ocean of sadness” she was trying to block through therapy, antidepressants, and sundry other remedies. “I always imagined that something was supposed to rescue me from the ocean,” Broder writes. “But maybe the ocean is its own ultimate rescue—a reprieve from the linear mind and into the world of feeling.”

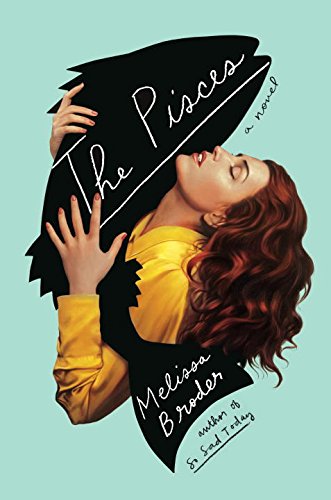

Enter her first novel, The Pisces, a surreal tale in fifty-five short chapters about Lucy, a Ph.D. candidate who spends a lot of time soul searching and staring into the Pacific Ocean from the rocks on Venice Beach. About halfway through the book, she meets a merman named Theo, a mythical creature that would seem to liberate Lucy from her prolonged depression. “Are you like a vampire?” she asks. “Are we in one of those teen vampire movies, only you’re a mermaid?”

In many wonderful ways, Broder shows us what such a reprieve from linear thinking actually looks like: Lucy’s stretch of living alongside the Pacific initiates an enchanting release of rationality and logic—and, in turn, an even fuller embrace of her ego, that part of the psyche most in touch with external reality. Early in the book, after we’ve learned that she’s landed at her sister’s house on Venice Beach for the summer following a bad breakup in Phoenix, Lucy looks out at the ocean and remarks: “The ocean swallowed things up—boats, people—but it didn’t look outside itself for fulfillment . . . it was self-sustaining. I should be like that. It made me wonder what was inside of me.”

Me is the operative word here. Remember Freud’s writing on “the oceanic feeling” in Civilization and Discontents? It’s a quality that might be best recapped as simply not giving a shit about anyone else but oneself. That classification sums up several of the frustrating characters in this book—from the constantly-triggered women in Lucy’s therapy group to the various men she hooks up with—all seasoned practitioners of turning things back on themselves. And it’s certainly the case with Lucy, a Pisces who is, stereotypically, “Never good at restraint.”

At times the inability of these characters to ever find fault in themselves, and their devotion to today’s wellness industrial complex, is just plain frustrating. But to this Broder adds hilarious and unflinching characterizations. Lucy’s ex, Jamie, is a geologist who is “handsome in an L.L. Bean travel vest sort of way.” Her frenemy from Phoenix, Rochelle, is “mid-forties with wiry, pubic-looking hair.” And her California group therapist Dr. Jude sports “yellowish teeth and a Dorothy Hamill haircut.” I could go on; the book is teeming with amusing portrayals of bad sex and even worse therapy sessions, and sometimes it makes a convincing case they are one and the same.

The book’s style is a natural extension of @sosadtoday, a melancholic Twitter account Broder began anonymously in 2012 while working on the social media staff at Penguin Random House. The so-called “doomsday rockstar” has since used the handle to merge observation and aggravation—with no reservation—spilling her guts for all to see. (She unveiled her identity in 2015.) Until 2016, @sosadtoday may have seemed like just another account of wintry puns, perhaps with a touch more self-loathing than other likeminded Twitterers. Yet when the So Sad Today book was published, with its brutal outpouring of honesty in raw and thoughtful prose, it became clear, if it wasn’t already, that Broder can do so much more than quick quips.

Acting as something of a counterbalance to Broder’s penchant for witticisms is Lucy’s academic thesis about the “spatial gaps” in poems by Sappho and whether they were meant as intentional negative space or not. (Throughout the book, Lucy refers to this as her thesis but she’s getting a Ph.D. so it should be her dissertation? Anyway…). Early on she admits, “It had dawned on me around year six that the thesis of my thesis, its whole raison d’être, was faulty. In fact, it was not just faulty. It was total bullshit.” And it is. But with this subplot Broder interlaces into The Pisces contemplations on the Ancient Greeks, though thankfully she never goes too deep and keeps it a light and brisk affair, not unlike @sosadtoday posts: “With their war, wine, poetry, and gods and food, they needed to get high. Maybe we all did.”

Drawing on the ancients is also how Broder gives a little more oomph to Lucy’s affair with Theo, in trying to connect the cosmic, interspecies sex the two have with a bigger picture: “We were connected now not only with all of human history—all the human lovers of the past—but with animal history as well.” But this is all very short lived—after Lucy hurts Theo by not disclosing that her time in Venice Beach is soon expiring, Theo transforms from a loving companion to just another overly needy (mer)man. Towards the end of the book, Lucy undergoes an Aristotelian reversal: She realizes, after a tragic (in the Ancient Greek style) turn of events that she is “objectively selfish and cruel.” She laments: “Suddenly it occurred to me that there really were gods who could smite us. The gods were just nature itself. If you didn’t follow the gods, you blew it. I had gone against nature. I had done it all wrong.”

Lucy then recalls the sage advice of Dr. Jude, a prophetic Tiresias-like figure, straight out of Sophocles. Responding to a woman in the therapy group who thinks she’s only hurting herself, Dr. Jude says no, adding, “There would be casualties . . . there were always casualties.” It might be Broder’s strongest thread connecting the book to the Ancient Greeks—it’s never just one person brought down in their plays but an entire family, a house, a people. Of course, collapse and widespread pain caused by entitled acts by humans (mostly men) has been happening, for, well, ever. And it all stems from that enduring, everlasting oceanic feeling.

Lauren O’Neill-Butler is a senior editor of Artforum.