Know thyself, the ancient philosopher said. Graph yourself, might be New York–based artist Andrew Kuo’s reply. By slice and dicing his stream of neurotic consciousness into flow charts, pie charts, and bar graphs, Kuo renders quotidian thoughts, worries, and speculations as quantifiable and official looking as GDP projections from the Congressional Budget Office. His images—marked by a gleefully saturated palette and puzzle-like complexity—play against staid expectations, calling to mind artists like Gene Davis and Barnett Newman rather than your Econ 101 textbook. The highbrow gloss notwithstanding, Kuo candidly depicts intimate preoccupations. Some are intellectual and reflective, such as “My Selected

- print • Apr/May 2011

- print • Apr/May 2011

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo open Poor Economics, their new treatise on development economics, by citing an experiment conducted on University of Pennsylvania students. Researchers paid students $5 to read one of two brochures about global poverty, then turned around and solicited a donation from the student. One brochure emphasized the magnitude of the problem using numbers—three million malnourished children in Malawi, eleven million in Ethiopia, etc.—while the other simply focused on the plight of one poor child, “Rokia,” whose fate could be transformed with the education and basic medical care that came with a donation of just a few

- print • Apr/May 2011

One might expect a fashion designer—that creature specially adapted to the vainest of industries, and, next to perhaps film production, the industry with the fuzziest math—to avoid mentioning a bankruptcy whenever possible. Diane von Furstenberg gets cagey when asked about her tour of duty on QVC after her dress line went bust, and Roberto Cavalli cried when he had to announce the cancellation of his Just Cavalli line after the licensee folded. Not Yohji Yamamoto. The Japanese designer mentions his bankruptcy on the first page of his memoir, My Dear Bomb, reprinting a letter of condolence from his friend Wim

- print • Apr/May 2011

In 1999, Woodstock’s thirtieth-anniversary festival ended in a wave of sexual assaults, rioting, and fires—an unlikely celebration of the original Woodstock’s “three days of peace and music.” The breed of angry male bands that dominated the festival and the airwaves that year with juvenile sexist resentment (as summed up by Limp Bizkit’s summer hit, “Nookie”) was a reminder that rock’s rebellion is often unfriendly to women. After Limp Bizkit’s inane and sloppy set (during which a gang rape allegedly occurred in the crowd), Rage Against the Machine, a precise and polished band—perhaps the most radical and influential protest group of

- print • Apr/May 2011

“For a collector . . . ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to things,” wrote Walter Benjamin in “Unpacking My Library.” “Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.” Benjamin’s distinction is illuminating in the context of debates over twentieth-century folklorist Alan Lomax. Lomax, who died in 2002, has a permanent place in the pantheon of American music—and yet the legacy of the Ivy League–educated white ethnomusicologist is complicated by his role as a collector of folk songs by poor, uneducated artists, many of them black. Lomax traversed the American

- print • Apr/May 2011

It’s almost impossible to write a book about our nation’s energy crisis that arouses in the reader any more excitement than what’s delivered in a maximum-strength barbiturate. I know this because I recently published one such book and found myself going out of my way, in my reporting rounds, to pursue the most extreme kind of high jinks—choppering out to ultra-deep oil rigs, spelunking into the Manhattan electric grid, even infiltrating a boob-job operation—all in the service of sustaining reader interest. While Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology may sound like a snoozefest, Alexis Madrigal manages—without

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

A PET PEEVE OF MINE is when people are shocked to find out that a great song was written relatively quickly. Of course it was, I want to say, before quoting one of many dog-eared passages in my worn copy of Natalie Goldberg’s Zen-creativity bible Writing Down the Bones, like, I don’t know, how about this one: “If you are on, ride that wave as long as you can. Don’t stop in the middle. That moment won’t come back exactly in that way again, and it will take much more time trying to finish a piece later on than completing

- excerpt • November 5, 2020

Every day for nearly a year, I immersed myself in chat groups and websites and forums where photos of lynchings were passed around like funny memes. Where “KILL JEWS” was a slogan and murderers were called “saints.” On the anniversary of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, I watched them celebrate Robert Bowers, the murderer of eleven Jews at prayer, like a hero and a friend. I listened to strangers talk about killing kikes every day. I listened to strangers incite violence and praise murder and talk about washing the world with blood to make it white and pure. I listened to

- excerpt • October 26, 2020

In 1975, the Black writer Ntozake Shange completed her verse play for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. In this work, which has become one of the classics of the modern feminist dramatic repertoire, seven African American women discussed their experiences of racism and sexism in society, and the creative strategies they devised to counter them. One of the characters, the “Lady in Brown,” spoke of her mind-blowing discovery of Toussaint Louverture as an eight-year-old child from St Louis. After entering a reading contest in her local library, she was swept away by how Toussaint had

- excerpt • October 13, 2020

“White people still run almost everything,” The New York Times’ Australian bureau intoned in 2018 in a devastatingly brutal report on cultural diversity in Australia’s workplaces. The whiteness above is noticed by workers below. Sonia, a forty-something woman of color (she asked me to omit her ethnicity for privacy reasons), has been employed in the same medium-sized private sector firm for a decade. She is a mid-level manager, a position she only achieved after nine years despite consistently positive performance reviews and above-average results that, she tells me, were frequently better than the men and white women promoted ahead of

- excerpt • September 16, 2020

When I was a graduate student in Texas, the first time I brought a story into workshop, a fellow student told me if I was going to “write about Indians,” I would need to separate my writing more from that of Louise Erdrich. Then this man misquoted from the beginning of Erdrich’s novel Tracks, ostensibly to show how similar it was to my story. At the end of workshop when it was my turn to speak, I corrected his misquotation and suggested in my most polite voice that perhaps to him “Indians” writing about snow all seemed the same. I

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

My husband and I canceled our spring-break trip because of the pandemic. His parents own a vacation house on a salt pond in Rhode Island that they let us use some weekends. Bummed about the cancellation and bored at home, we headed up there for a long weekend on Wednesday, March 18, thinking we’d return that Sunday or Monday. Coincidentally, that was the week that New York became the worldwide epicenter of COVID-19. Now it’s August and we’re still here.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

Spread from Duro Olowu: Seeing. Left, inset: Richard Serra, Prop, 1968. Right: Dawoud Bey, A Boy Eating a Foxy Pop, 1988. © Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Duro Olowu has a flair for unlikely combinations. A single collection by the Nigerian-born designer might include flowing candy-striped silks, metallic floral brocades, crushed velvets in high-voltage hues, […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

In November 1961, a closeted gay man in a well-tailored suit went to see an unsigned and relatively new musical group performing at a Liverpool club called the Cavern. “I was immediately struck by their music, their beat, and their sense of humor on stage—and . . . when I met them, I was struck again by their personal charm,” Brian Epstein would write in A Cellarful of Noise, his 1964 memoir about the band he would soon manage, make over, and turn into mop-topped superstars. Teasingly, referring to the open secret of Epstein’s private life, John Lennon suggested an

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

PORTIONS OF CLAUDIA RANKINE’S Just Us first appeared in the New York Times Magazine and were posted online with the clickbaity headline “I Wanted to Know What White Men Thought About Their Privilege. So I Asked.” In the article—now the second section of the book, after some introductory poems—Rankine relates some of the material covered in a class called Constructions of Whiteness that she teaches at Yale. As part of the class, her students sometimes interview strangers about race. “Perhaps this is why . . . I wondered what it would mean to ask random white men how they understood

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

TWO FIGURES OVERLOOK A SACRED RIVER: both qualify as students, yet one is more experienced by far. He attempts to bridge the difference with a lesson. Pointing to the wastelands on the right bank, he defines it as sunyata, the void. Then, turning, points at the city opposite. An enormous maze of temples and houses, the dwellings of deities and castes: that is maya, illusion. “Do you know what our task is?” A test. “Our task is to live somewhere in between.” We have two versions of the scene, but in each case the younger student is described as “terrified.”

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

“IT WAS HIS QUOTABILITY,” observed the critic Clive James, “that gave Larkin the biggest cultural impact on the British reading public since Auden.” What comes to mind? The opening lines from “Annus Mirabilis,” certainly—“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three”—but if there is one Philip Larkin quote even better known, it would surely be: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.”

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

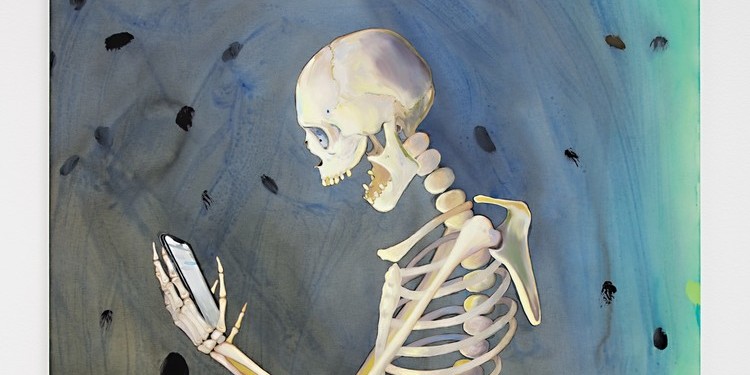

I QUIT TWITTER and Instagram in May, in the same manner I leave parties: abruptly, silently, and much later than would have been healthy. This was several weeks into New York City’s lockdown, and for those of us not employed by institutions deemed essential—hospitals, prisons, meatpacking plants—sociality was now entirely mediated by a handful of tech giants, with no meatspace escape route, and the platforms felt particularly, grimly pathetic. Instagram, cut off from a steady supply of vacations and parties and other covetable experiences, had grown unsettlingly boring, its inhabitants increasingly unkempt and wild-eyed, each one like the sole surviving

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

“A DISAPPOINTED WOMAN should try to construct happiness out of a set of materials within her reach,” William Godwin counseled Mary Wollstonecraft after she tried to kill herself by jumping off a bridge. Virginia Woolf liked to read “with pen & notebook,” a generative relationship to the page. Roland Barthes had a hierarchical system with Latinate designations: “notula was the single word or two quickly recorded in a slim notebook; nota, the later and fuller transcription of this thought onto an index card.” Walter Benjamin urged the keeping of a notebook “as strictly as the authorities keep their register of

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

IN FEBRUARY 2005, the literary theorist Sianne Ngai published Ugly Feelings, a book she described as a “bestiary of affects” filled with the “rats and possums” of the emotional spectrum. Instead of looking to the classical passions of fear and anger, Ngai, then an English professor at Stanford University, wanted to explore what she called “weaker and nastier” emotions. The book is divided into seven chapters, each focusing on a single “ugly feeling” such as envy, anxiety, irritation, and a hybrid of boredom and shock she termed “stuplimity.” Based on Ngai’s graduate dissertation, Ugly Feelings (an unusually laconic title for